3. Framing of interventions

Framing refers to the information we share, how we present it and also what information we do not share.

All presentation of information is, inevitably, framed.

Careful framing can be applied to all levels of communication and engagement with the public to transmit key messages so that they land effectively and resonate with those we are trying to reach.

This section shows how framing can be used to communicate the links between the built environment and health, aid communication of the rationale for change, emphasise potential health impacts of introducing change, and appeal to people’s emotions.

Lessons are drawn from framing literature and applied to framing information around LTNs and related interventions.

3.1 WHY DOES FRAMING MATTER?

If a policy is met with negative public perception, there is less political willingness from policy makers for it to be implemented, despite potential health benefits – Neufeldt, 2024

Framing can help communicate the (health) rationales behind policy and related interventions in a clear way.

- This promotes equity of access to information by ensuring public understanding of an issue

- It can enhance acceptability of messaging amongst the public and therefore increase opportunities to achieve positive change

- Where topics may be emotionally sensitive – such as in relation to chronic illnesses or addressing obesity – framing can help carefully craft communication around data and associated policies without causing unnecessary upset or sense of individualised blame for such health conditions

For more background information on framing and framing strategies see FrameWorks UK (2022) and Victorian Health Foundation (Victorian Health Foundation, 2021)

3.2 ENTRY POINT TO FRAMING

Considerations to framing should begin by recognising your audience. When communicating change in the context of potentially controversial / polarised interventions – such as LTNs – messages should appeal to those who already support, or can be persuaded to support, rather than those who have a fixed position opposing the intervention.

Supporters who are already likely to be on board

Persuadables who are undecided and could change their mind depending on information presented

Those who are strongly against the proposed change and unlikely to change their mind

This means focusing messages to appeal to supporters and potentially shift persuadables into supporting change, rather than messages that try to appeal to both opponents and persuadables which have been less effective in the context of promoting active travel initiatives, for example (Victorian Health Foundation, 2021), and/or attempting to mythbust any existing misconceptions (See Section 3.3, recommendation 6, below).

3.3 FRAMING RECOMMENDATIONS AND HEALTH-BASED EXAMPLES

These six recommendations are applicable to a range of interventions and should be adapted to specific audiences to enable more effective communication (Keller and Lehman, 2008; Eljiz et al., 2020).

When planning the information you will be framing, consider:

- who you can reach, and through what channels

- what information they may already be engaging with, and

- what they may expect from your messaging.

Arguments need to be robust enough to stand, and simple enough to get across.

NB. It may be necessary to reflect on how information is framed/reframed for and communicated to different publics, including various age groups and those from different communities. A ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach is unlikely to land with all socio-demographic groups.

FrameWorks (2022) describe how persuasive narratives have three ingredients:

- they explain what the issue is

- they show why the issue matters

- they show how the issue can be changed

1) Present the issue and show why it matters

Clearly explain why change is necessary

2) Show change is possible

Share tangible options/solutions which demonstrate that there is another way (intervening) instead of letting the issue/status quo continue

3) Appeal to people’s values and emotions

Emphasise values such as shared health benefits for everyone and the difference this can make – rather than relying on economic arguments and data

4) Humanise the story

Share real people’s experiences within your narrative to engage and create a sense of relatability. This can also be reflected in the language chosen to help reduce a sense of ‘us’ and ‘them’

5) Use positive, ‘gaining’ language

Explain what there is to gain and new opportunities of change, rather than what may be lost.

6) Focus on clear messaging rather than just myth-busting

Share a coherent and consistent narrative. Drawing attention to myths or misinformation can be counterproductive.

Present the issue and show why it matters

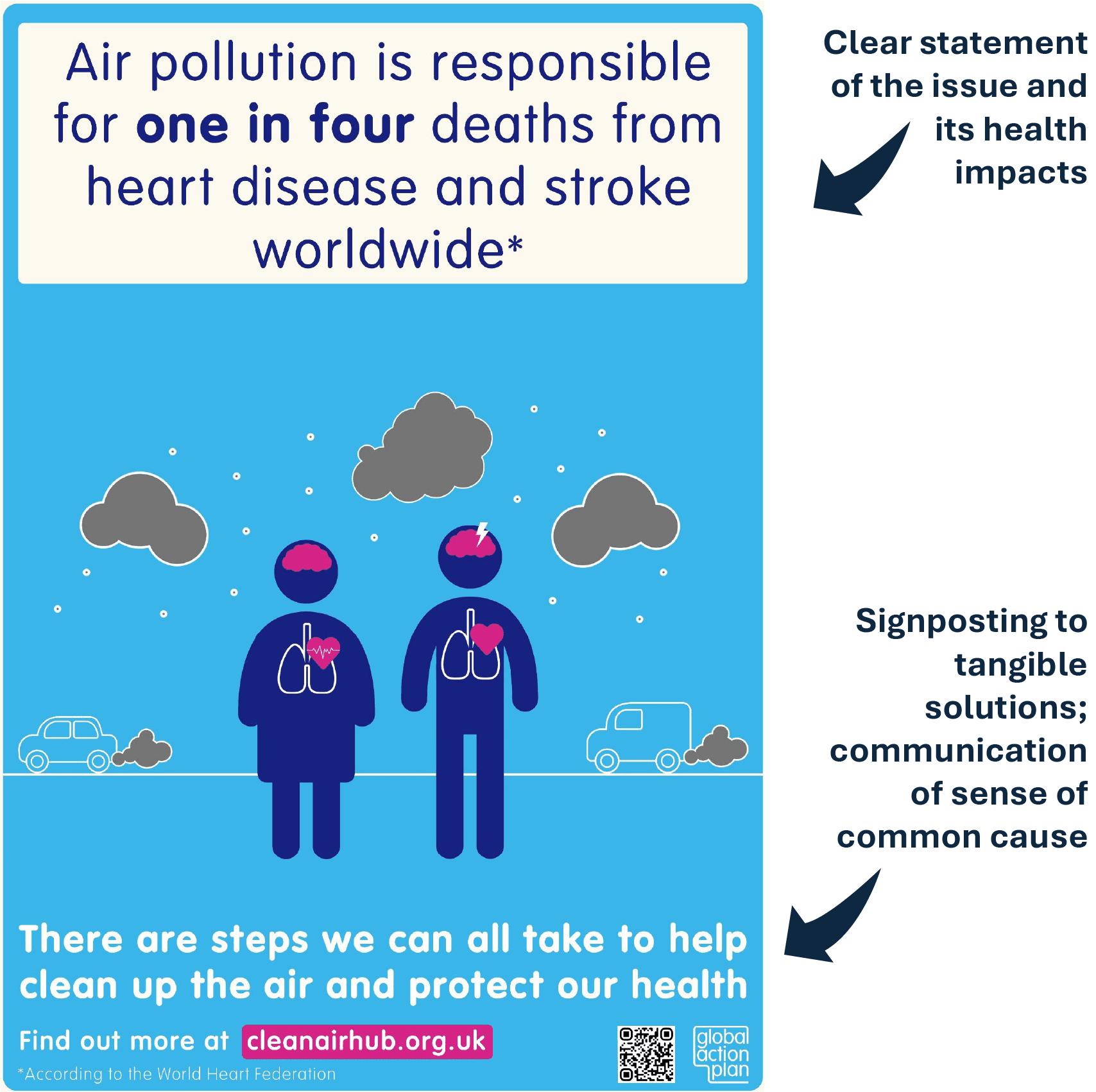

Concept and practice

To get people on board with an idea, they need to understand what the key issue being presented is, and why it matters. Leading with clear statements gets attention.

Evidence and reasoning should be clearly explained and jargon avoided, ensuring that information is accessible.

Presentation of problems should be balanced with tangible solutions (see Recommendation 2).

Health context

FrameWorks (2022:6) provide examples of how impactful statements can be used to grab attention:

‘Life expectancy is not the same across the UK. In some places people are dying earlier…’

‘Too many young people are dying too young, because of …. ‘

Show change is possible

Concept and practice

Tangible solutions show that there is an alternative to the (harmful) status quo, and the role that a proposed change or intervention can play in delivering improvement.

- Avoid talking about limited resources to deliver change – this creates thinking that decisions will be made which benefit one group at the expense of another for this to be achieved

- Visual media can help demonstrate realistic change and scale/impact of any proposted intervention in an accessible way. This could be artist impressions or pictures from similar past projects.

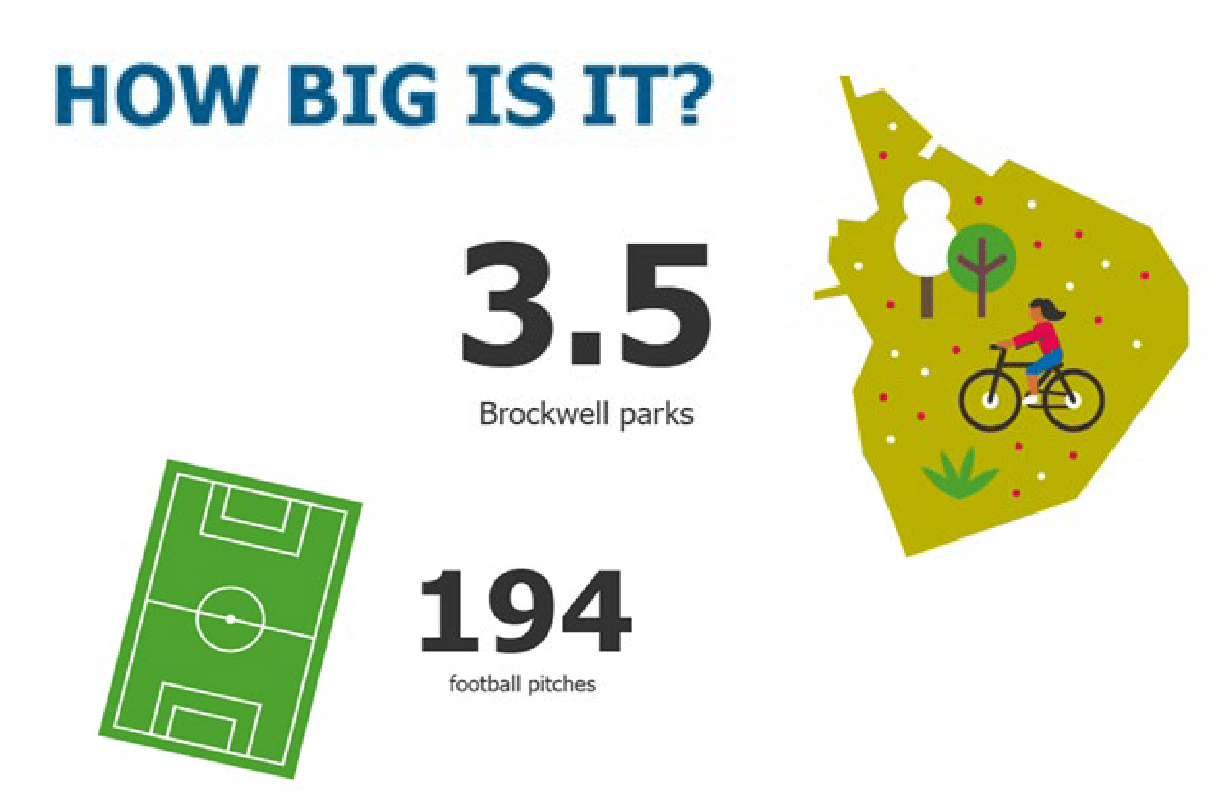

▲ Image of relatable and local comparisons to understand scale of initiative change in Lambeth Kerbside Strategy (2023b)

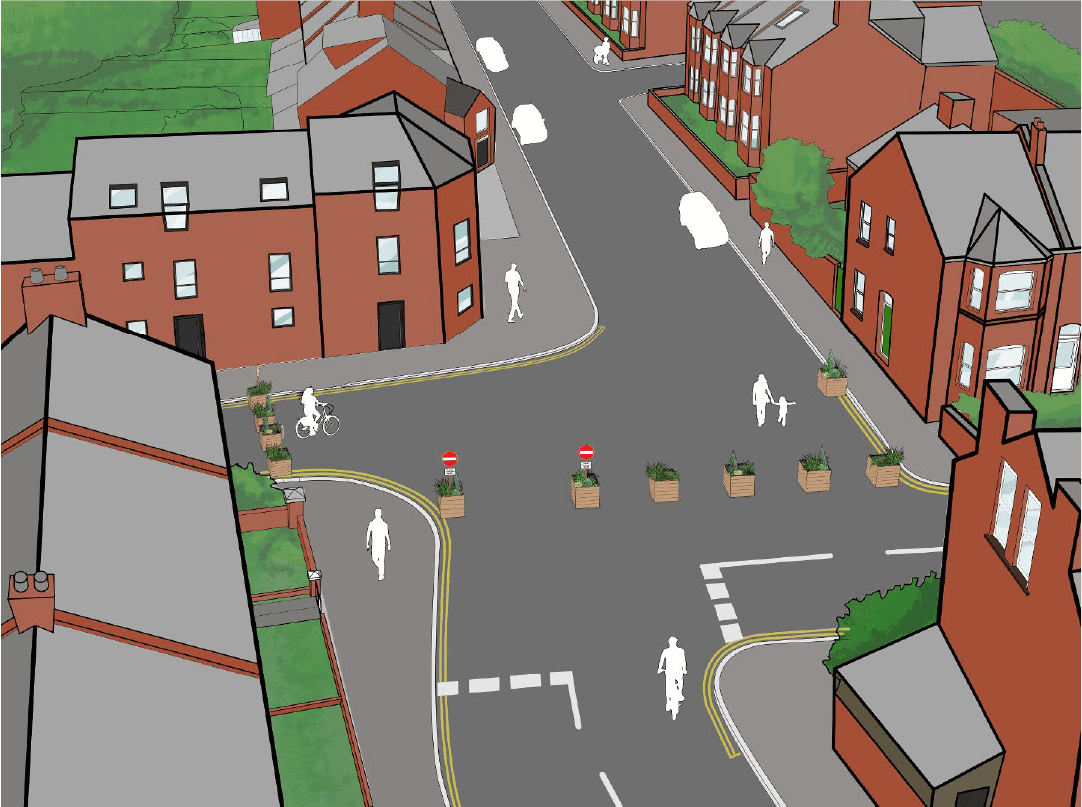

▲ Artist visualisation of ‘modal filters’ Heavitree and Whipton, Exeter LTN

(Devon County Council, 2024)

Health context

- Solutions provide hope when talking about sensitive issues such as non-communicable disease

- Avoid referring to the strain on the NHS that poor health brings. This can create ideas that some groups are creating a burden and less deserving of health care and change than others and can (re)produce stigma (FrameWorks, 2023)

. - Visualisations can help communicate health impacts across literacy and language barriers, enabling inclusive and accessible information (Sleigh and Vayena, 2021)

Appeal to people’s values and emotions

Concept and practice

Focus on promoting equity, accessibility, care for others, showing that everyone can benefit from a proposed change.

Not only are these values hard to argue with, but they provide a common goal that appeals to everyone, bridging the ‘us and them’ gap between divided audiences (Neufeldt, 2024).

Data can be used to support a story, but if the audience needs to make their own links between cause and effect, there can be misinterpretation. Relying on economic data can also be off-putting – focusing on values prompts a greater sense of care for a cause than a proposed financial saving to government or the NHS.

“Values and emotions trump facts”

– Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, 2021:7

Built environment / LTN context

Emphasise that streets are for everyone to access and benefit from. This challenges motornormativity.

- Refer to ‘streets’, not ‘roads’ – this creates imagery of the whole streetscape and all users as being affected and important to consider

- Avoid focusing on parts of the street as ‘space’ – Instead of talking about divided spaces/segments in the street, present the street as a shared space for multiple users. This avoids ideas of (re)allocation and territory where one group benefits at the expense of another. For example, say “improving and widening pavements” instead of “increasing pavement and pedestrian space”

Health context

Try ‘common cause’ framing such as

“Everybody deserves access to…

- Clean air

- Space to walk around and exercise safely…. “

Humanise the story

Concept and practice

Humanising an issue makes it feel real by showing a relatable experience and/or creating an emotional connection. This helps reduce any sense of ‘us and them’ competitive thinking and showing similarities, as people, between different (imagined) groups.

This approach was carried out successfully in TRUUD’s Living in Unhealthy Places and ‘It’s a matter of life or death’ short films which show how the built environment affects the physical and mental health of different families in various ways, incorporating lay knowledge into communication and highlighting the need for change.

As well as the use of films, stills and other images, narrative quotes can also help humanise stories and break up heavy text.

▲ Tabby and Elsie talk about their Active Neighbourhood in Manchester

(Transport for Greater Manchester, 2025)

Built environment / LTN context

In Active Travel initiatives, referring to ‘people driving/ cycling / walking’ instead of ‘drivers/ cyclists’ not only serves as a reminder that individual people fall into multiple categories but also avoids prompting any prevailing stereotypes of particular kinds of drivers and cyclists. This reminds your audience that people do not fit into homogenous groups and particular interventions can bring health impacts and benefits to be experienced by everyone.

Using quotes and videos of people speaking can help humanise an issue and tell a story. For example, in Manchester’s Active Travel Neighbourhood, residents described the ways their life has been improved by the intervention (see short film below). This shows change is relatable and credible.

Need for sensitivity when referring to health

Health is experienced individually, and can be linked to individual behaviour, but also relates closely to the built environment and structural and social determinants of health. Care needs to be taken in communicating and framing information about stigmatised health impacts such as obesity. Acknowledging that our health is affected by our built environment, not just individual ‘choices’, avoids exacerbating stigmatization of a certain community/demographic group/geographical area and prevents ‘victim-blaming’.

Use positive, gain-framing language

Concept and practice

Make positive statements about opportunities and potential benefits, rather than focusing on what may be lost.

Kahneman and Tversky (1979) found that when people were presented with two equal deals, they were more likely to choose the one that presented the impact as potential gains, rather than potential losses. Therefore, framing should include ‘more of’, rather than ‘less of’ phrasing.

Instead of this… ▶

Modal filters in Edgbaston, Birmingham (University of Birmingham, 2024)

◀ Try this…

‘Road open to… ‘ LTN modal filters (Guttridge-Hewitt, 2025 )

Built environment / LTN context

In LTNs, you can explain this by referring to there being

- more opportunities to walk and cycle

and how

- streets and roads are open to people

rather than being closed to cars.

This reminds us that streets are for everyone and supports recommendation 3 in appealing to values. This is not only strategic framing, but avoids falling into the realms of motornormativity and misinformation by referring to closure when the street/road is still open and accessible, just by different modes of travel.

Health context

When looking at the framing of health issues such as obesity, positive language that focuses on improvement can achieve better outcomes than dwelling on stigmatising characteristics. For example, highlighting the need to improve children’s health, rather than focus on children’s obesity (see FrameWorks, 2023).

Avoid myth-busting

Concept and practice

It seems tempting and sensible to correct any prevailing misinformation, but this can merely reiterates untrue beliefs because the more familiar a statement is, the more credible it may seem.

Instead, information should be

- clear and memorable

- consistent

- supported with context to help readers meet intended understanding and conclusion

- highlight where data / information has come from to improve credibility.

(Peter and Koch, 2015; Frameworks, 2022)

Built environment / LTN context

Some of the common concerns and misconceptions around LTNs is that they will

- displace motor traffic and associated pollution

- negatively impact local businesses

- negatively impact those with disabilities and/or those in less affluent areas

- increase response time for emergency services

Some of these prevailing concerns can be addressed without myth busting but drawing on evidence:

- While there may be initial displacement, people adjust their travel behaviour so not to disturb the traffic system (Borowska-Stefańska et al., 2023)

- Net pollution is reduced by less net car use, and opportunities for new green infrastructure to improve air quality

- Local businesses benefit from increased local footfall, where in a Department for Transport survey, residents report feeling either an increased or the same likelihood as visiting businesses within an LTN change at all. (Logan et al., 2021:13, 38; Mason, 2021)

Health context

Instead of

“People think health is our own responsibility – but actually it is greatly impacted by the options and opportunities available”

Try,

“The options and opportunities available to us shape our health. Whether we can access healthy food in the shops where we live, to whether we have safe spaces to walk and exercise”

(Frameworks, 2022)

Section 3: Key points and learning

Key points

- Framing refers to what information we share, how we present it, and the information we choose to not share

- Careful consideration to framing can help communicate key messages in (more) effective ways

- Enhancing the acceptability of messaging creates entrypoints for introducing ideas around positive, health-related change – this is particularly relevant to new interventions, including those such as LTNs which might be perceived negatively or be considered controversial

Learning

- Focus on ‘persuadables’ in the framing of information

- Show why the issue matters by clearly explaining why change is necessary

- Show change is possible with tangible solutions and options, and how an intervention can help achieve this

- Use positive, ‘gaining’ language to demonstrate the opportunities available, rather than what may be lost or compromised

- Appeal to people’s emotions and values – humanising the story, and creating a sense of relatability helps create an idea of a common cause

- Share a clear, consistent narrative, rather than waste efforts on myth-busting

REFERENCES

- Borowska-Stefańska, M., Felcyn, J., Gałuszka, M., Kowalski, M., Majchrowska, A., & Wiśniewski, S. (2023). Effects of speed limits introduced to curb road noise on the performance of the urban transport system. Journal of Transport & Health, 30, 101592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2023.101592

- Eljiz, K., Greenfield, D., Hogden, A., Taylor, R., Siddiqui, N., Agaliotis, M., & Milosavljevic, M. (2020). Improving knowledge translation for increased engagement and impact in healthcare. BMJ Open Quality, 9(3), e000983. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2020-000983

- FrameWorks . (2022). How to talk about the building blocks of health: A toolkit. In FrameWorks UK. https://frameworksuk.org/wp-content/uploads/HEAJ9448-Communicators-Toolkit-220725-2.pdf

- FrameWorks. (2023). 5 tips for communicating about children’s health & food. FrameWorks UK. https://frameworksuk.org/resources/5-tips-for-communicating-about-childrens-health-and-food/

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: an Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

- Keller, P. A., & Lehmann, D. R. (2008). Designing Effective Health Communications: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 27(2), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.27.2.117

- Lambeth Council. (2023). Lambeth’s Kerbside Strategy | Executive Summary. Lambeth-Kerbside.org. https://lambeth-kerbside.org/

- Logan, T., Mcphedran, R., Young, A., & King, E. (2021). Low Traffic Neighbourhoods Residents’ Survey Report (pp. 1–57). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60f84675d3bf7f56872f4baf/low-traffic-neighbourhoods-residents-survey.pdf

- Neufeldt, J. (2024). How Media Framing Shapes Opinion of Environmental Policy: The Case of ULEZ. The Cambridge Journal of Climate Research, 1(2), 1–21.

- Peter, C., & Koch, T. (2015). When Debunking Scientific Myths Fails (and When It Does Not). Science Communication, 38(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547015613523

- Sleigh, J., & Vayena, E. (2021). Public engagement with health data governance: the role of visuality. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00826-6

- Victorian Health Foundation. (2021). Framing walking and bike riding message guide. Www.vichealth.vic.gov.au. https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/VBM-Framing-Walking-Bike-framing—message-guide.pdf

Funding statement

Our partners

Funding statement

This work was supported by the UK Prevention Research Partnership (award reference: MR/5037586/1), which is funded by the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Health and Social Care Research and Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Natural Environment Research Council, Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), The Health Foundation and Wellcome.

Our partners

v2.23