1. Introduction

This toolkit provides information and guidance for those responsible for designing public engagement around built environment interventions. While it has a particular focus on early, health-informed engagement related to traffic and street improvements in the UK, the learning and guidance shared can be applied to many different contexts.

Our principal audience is officers working within local authorities or combined authorities in the UK who hold particular responsibility for designing traffic and street improvement interventions and engaging with the public. However, much of the toolkit content is also relevant to other practitioners and specialists involved in communicating and engaging with the public, both in the UK and wider settings.

Note on presentation: relevant hyperlinks are provided on the site, highlighted in bold purple text.

1.1 WHY THIS TOOLKIT?

The toolkit was produced by the Public Involvement team on the TRUUD project –‘Tackling Root Causes Upstream of Unhealthy Urban Development’ (TRUUD). TRUUD involved researchers across different disciplines collecting evidence and designing and testing interventions aimed at enhancing the ways in which urban planning and decision-making in the UK contribute to the prevention of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). See TRUUD 2025. The TRUUD Public Involvement team, based at the Centre for Public Health and Wellbeing at the University of the West of England (UWE Bristol) worked specifically on:

- enabling more meaningful input from communities during public engagement around urban planning and decision-making; including

- bringing lay knowledge* about the health impacts of the built environment closer to decision-makers

This toolkit shares some of the key learning from their work. It draws on a wide breadth of sources and resources, including a literature review of public engagement best practice, framing theory analysis, a grey literature review of Low Traffic Neighbourhood (LTN) schemes in the UK, an applied review of digital tools used in public engagement, observations of public engagement in practice (both in person and online), and the testing of co-produced materials aimed at facilitating deliberative, health-informed public engagement (see Section 4).

*By ‘lay knowledge’ we refer to knowledge and understanding held by lay public/s based on their own experiences

1.2 DEVELOPMENT OF THE TOOLKIT

Our work on the toolkit involved input from various stakeholders:

- The TRUUD Public Advisory Group (PAG). The PAG provided insight and perspectives from the public and advised researchers across the course of the TRUUD project. They were co-designers of the engagement materials which were tested and are shared in the toolkit (see Section 4). The PAG also reviewed all toolkit content.

- Knowle West Media Centre which advised on public engagement approaches and facilitated our ‘test’ engagement event.

- TRUUD’s Researchers-in-Residence at Bristol City Council (BCC) and Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA). These researchers facilitated links with relevant officers at BCC and GMCA who shared some of their insights and experiences around the design of traffic and street improvements.

1.3 WHAT DO WE MEAN BY PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT?

Public engagement – sometimes also referred to as community engagement – is a collaborative process whereby decision-makers work with the public in the planning and design of changes to the built environment.

This can involve the sharing of information, generation of initial ideas, and the refinement of briefs all the way through to project implementation (QOLF, 2024). Engagement aspires to incorporate lay views and lay values in the decision-making process (Open University 2025).

Public engagement can be distinguished from public – or community – consultation – which is a more formalised process and method where feedback is sought on specific planning/ project proposals.

Our toolkit focuses on the crucial early stages of engagement when introducing and discussing changes to the built environment. However, some of the lessons outlined in the toolkit are also relevant to subsequent stages, including consultation.

1.4 HEALTH IMPACTS OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

There is growing evidence of the links between the built environment and population health.

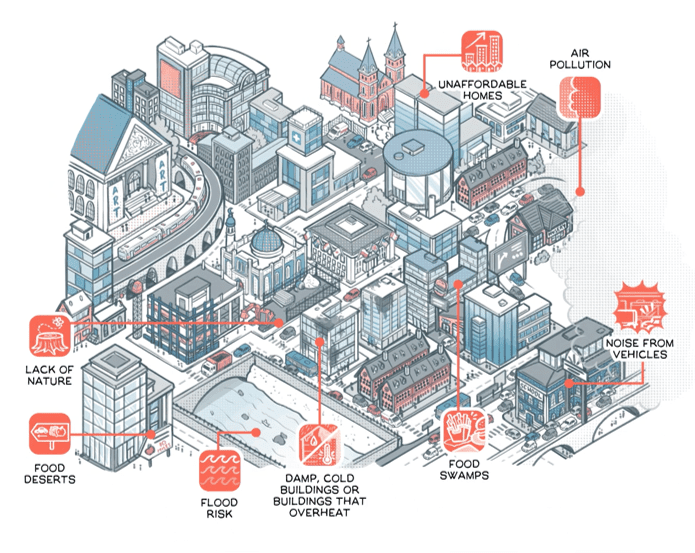

▲ Diagram of how the physical urban environment can impact human health (from the ‘Changing decisions upstream with TRUUD’ video produced by We Are Cognitive TRUUD, 2025)

- Non-communicable diseases (NDCs) – that is diseases people cannot catch from others – such as heart disease, asthma and poor mental health from air and noise pollution as well as obesity and other impacts from sedentary lifestyles – are on the rise (Freestone and Wheeler, 2015; Carmichael et al., 2019; WHO, 2025).

- The impacts of housing quality and neighbourhood design on health are increasingly recognised. These include the effects of air and noise pollution; damp, cold and risk of overheating; overcrowding due to unavailable/unaffordable housing; lack of green space and surrounding food environments (Bird et al., 2018).

- Widening differences in life expectancy have been caused by unhealthy built environments in which some people reside (Bird et al., 2018 ; TRUUD, 2023; WHO, 2025).

1.5 HEALTH IN BUILT ENVIRONMENT DECISION-MAKING

“Communication between built environment and health professionals is essential”

Bird et al., 2018: 11

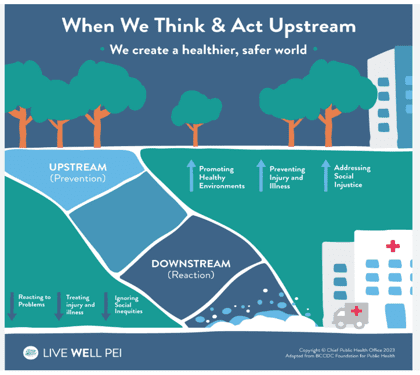

Addressing the links between the built environment and physical and mental health requires focusing on the prevention of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) through strategic decision-making ‘upstream’ by national government, local government and other actors.

Yet barriers exist to translating known links and impacts into upstream decision-making.

- Poor understanding of the range and complexity of physical and mental health and wider societal impacts among certain stakeholders. This is related to limitations in how data and evidence are currently used to enhance understanding (Sleigh and Vayena, 2021).

- Health data and academic evidence are not readily accessible and translatable. It takes time and expertise to interpret relevant national and local data to support policy implementation (Carmichael et al., 2019; White, 2022).

- The evidence basis informing policy and practice is not shared comprehensively.

- Both quantitative and qualitative evidence based on lived experience are needed to convey the complex range of impacts of the built environment (Bates et al., 2023). Lay knowledge is an important aspect of qualitative evidence (TRUUD 2024a).

- Data and evidence are often not routinely shared in communication and engagement with the public.

- ‘Silo thinking and operational ‘fiefdoms’ prevent collaboration across government departments and wider partners (TRUUD 2024b).

- Political reluctance to introduce policies and associated interventions that may have a negative public perception – and hence implications for elected officials – such as new traffic restrictions to improve air quality (Neufeldt, 2024).

1.6 INTRODUCING IMPROVEMENTS TO TRAFFIC AND STREETS

Various policy-based initiatives, such as Clean Air Zones (CAZ), Ultra Low Emission Zones (ULEZ), 20 mph schemes and Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) have been introduced in the UK with a core aim of preventing non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Their objective is to promote population health and wellbeing through reducing air pollution, as well as, in certain cases, enhancing safety and enabling/ increasing greater physical activity through ‘active travel’ (TfL, 2023; DEFRA, 2019; Sport England, 2023:5).

Here, we detail some of the common, contextual factors which have posed barriers to the introduction of these initiatives.

CAZ Sign via Duffield, 2021

Wider social context

Motornormativity

Motornormativity is ‘a shared bias whereby people judge motorised mobility differently to other comparable topics. This works against societies addressing climate and public health crises effectively’ (Walker and Brömmelstroet, 2025:1). This unconscious bias, also referred to as ‘car blindness’, leads people, including policy makers, to neglect the negative externalities brought about by car use and car travel norms, and resist changes to these norms even when these changes could bring public health benefits (Walker et al., 2023).

Motornormativity

A shared bias whereby people judge motorised mobility differently to other comparable topics

‘Infodemic’: spread of (false) information by social media

Operationalising national level policies at a local level has faced specific challenges, not least the politicisation of certain interventions by some politicians. For example, polarising arguments about a ‘war on motorists’ emerged in the early 2020s, which undermined interventions aimed at changing car travel norms and fuelled division (Perry et al., 2024). More recently, the politicisation of the environmental arguments for change has emerged (Boykoff, 2008;Neufeldt, 2024), with the Reform Party making ‘net stupid zero’ a campaign issue (Catt, 2025), for example. UK media ‘conflict’ framing of interventions such as ULEZ have contributed to this politicisation and influenced public perceptions (Neufeldt 2024).

National to local level transition and politicisation

Social media is a critical space where the public both access and circulate information and opinions, and for many is replacing news media as a core source of information. This now-ubiquitous space also facilitates an increased spread of false information (Wang et al., 2020; Golder and Graham, 2024), both misinformation and disinformation.* Myths/false information about the rationales behind and potential impacts of different built environment schemes can influence public perceptions and fuel opposition (Samantray and Pin, 2019 ; Ashton, 2024), posing direct challenges to their introduction. Yet it has been argued that this problem has, to some extent, been caused by a failure in how national and local government has approached policy-making and public engagement and engaged with local information systems (Perry et al., 2024). Important lessons can be learnt from experiences to date.

*Misinformation is incorrect or misleading information. Disinformation is false information which deliberately intends to mislead

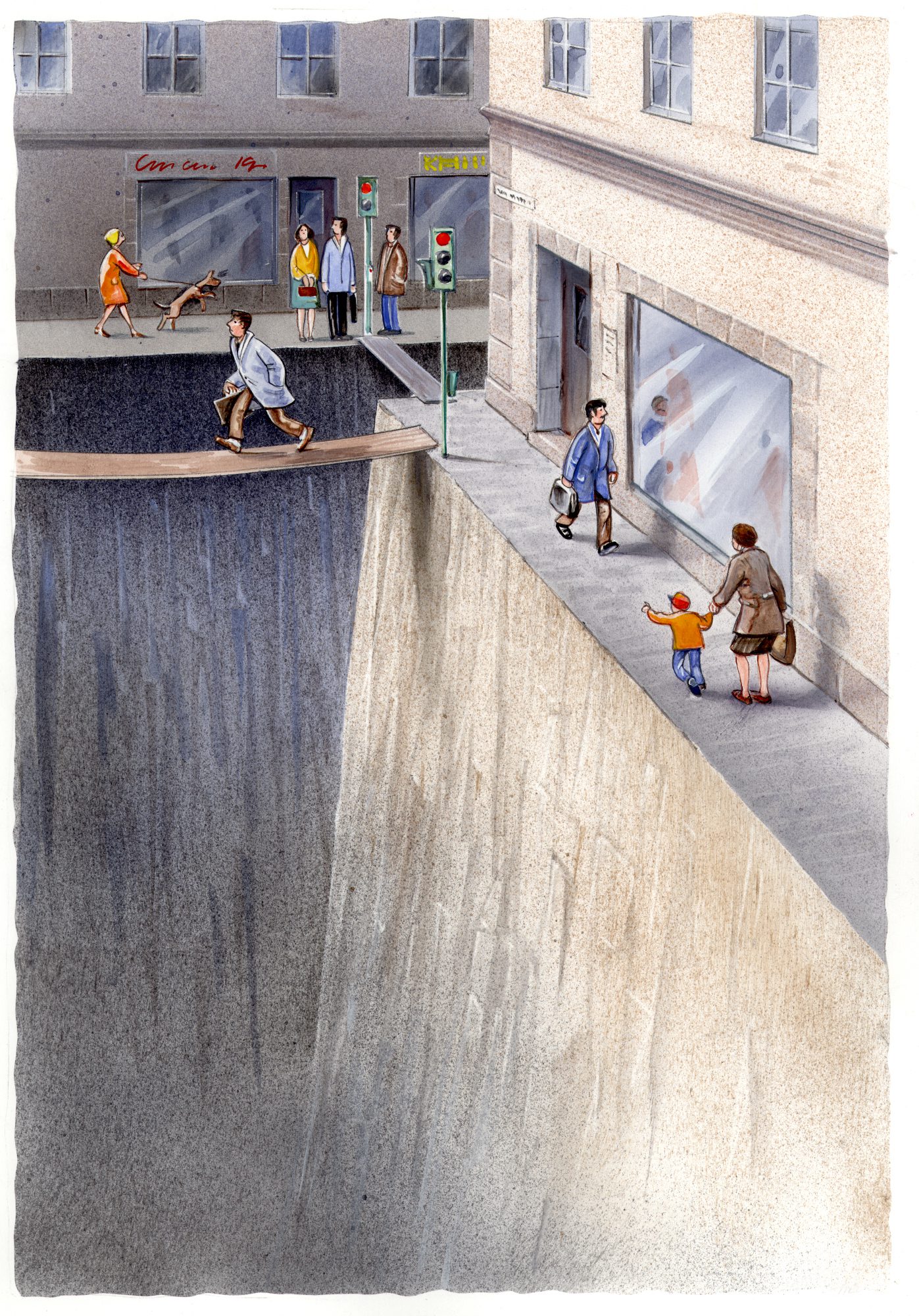

▲ Illustration of dominance of cars in public space and how this affects pedestrians. Karl Jilge, reproduced with permission of the artist

Communication of evidence

Strategic built environment interventions related to traffic and streets can contribute to reducing pollution and provide both physical and mental health benefits due to less polluted and stressful streets as well as increases in physical activity. Given the relatively recent introduction of many schemes, evidence of impact is nascent. In the case of the London ULEZ a 27% reduction in nitrogen dioxide was measured between 2019- 2024 (GLA, 2025), with significant implications for cardiovascular and respiratory conditions. Despite these positive benefits, the health evidence relating to the impacts of such interventions has not yet been fully optimized through strategic communications.

The ‘active travel’ concept

Not all members of the public are able to embrace cycling and more vigorous forms of mobility. Recognising this and broadening the concept of ‘active travel’, and how it is presented in public-facing communication related to traffic and street improvements, may better capture different ways of moving from place to place and their benefits (Cook et al., 2022). In any conceptualisation and communication of change and its rationale it is essential that it is comprehensible to the general public as well as being inclusive and does not risk alienating or marginalising certain publics.

Safety concerns

Sense of safety can be a barrier to public adoption of schemes promoting more active travel, such as cycling. For example, around half of respondents of a 2021 Department for Transport survey reported they would be encouraged to walk and cycle more if roads were safer (DfT, 2023). Supportive infrastructure and rigorous regulation and enforcement around new schemes are required to address such concerns.

Opposition to/rejection of financial and personal costs

These include charges associated with Clean Air Zones and penalties for using ‘bus gates’ in Low Traffic Neighbourhoods – particularly in a context of widening inequalities in the UK (Neufeldt, 2024). The personal inconvenience and costs faced by those whose car travel is restricted/ journey times increased can also constitute a new burden.

This requires careful responses, including intervention-specific measures to reduce the burden on the poorest and most vulnerable so they are not disproportionately affected.

All of these factors are relevant to how new initiatives are first introduced to the public and then subsequent engagement strategies towards collaborative design and implementation.

SECTION 1: TAKE AWAY POINTS

- Prevention of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) related to the built environment can only take place through decision-making ‘upstream’ by national and local government and other actors, including private sector stakeholders. The translation of known links and impacts into responsive decision-making is essential.

- Improved understanding of the need for strategic interventions is required amongst all stakeholders. Different forms of evidence of the multiple relationships between the built environment and physical and mental health need to be shared.

- The rationale related to any intervention needs careful explanation and presentation through ‘local information ecosystems.’

- The introduction of any intervention aimed at preventing NCDs needs to be sensitive to a range of key contextual factors affecting how these are understood and accepted. The social and economic costs at local level – particularly costs to the most vulnerable and disadvantaged – need to be anticipated and addressed early on.

- The ways in which early communication and engagement with the public is designed affect how change is introduced and how the public consequently understands and responds. Creating a context for meaningful early exchange and decision-making is more likely to have a positive outcome.

In the following section we explore the process and some of the challenges to date from introducing Low Traffic Neighbourhood schemes in the UK before examining implications for future public engagement.

REFERENCES

- Bates, G., Ayres, S., Barnfield, A., & Larkin, C. (2023). What types of health evidence persuade policy actors in a complex system?. Policy & Politics, 51(3), 386-412. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557321X16814103714008

- Bird, E. L., Ige, J. O., Pilkington, P., Pinto, A., Petrokofsky, C., & Burgess-Allen, J. (2018). Built and natural environment planning principles for promoting health: an umbrella review. BMC Public Health, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5870-2

- Boykoff, M. T. (2008). The cultural politics of climate change discourse in UK tabloids. Political Geography, 27(5), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2008.05.002

- Carmichael, L., Townshend, T. G., Fischer, T. B., Lock, K., Petrokofsky, C., Sheppard, A., Sweeting, D., & Ogilvie, F. (2019). Urban planning as an enabler of urban health: Challenges and good practice in England following the 2012 planning and public health reforms. Land Use Policy, 84, 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.02.043

- Catt, H. (2025, May 2). How the political consensus on climate change has shattered. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cx20znjejw1o

- Cook, S. Stevenson, L., Aldred, A., Kendall, M., Cohen, T. (2022). More than walking and cycling: What is ‘active travel’? Transport Policy, Vol 126: 151-161,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2022.07.015. - DEFRA. (2019, January 14). Clean Air Strategy 2019: executive summary. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/clean-air-strategy-2019/clean-air-strategy-2019-executive-summary

- Department for Transport. (2023). Active Travel in England Department for Transport, Active Travel England REPORT (pp. 1–14). https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/active-travel-in-england-summary.pdf

- Freeman, E., Bin Jalaludin, & Thompson, S. (2011, December 2). Healthy Built Environments: Stakeholder engagement in evidence based policy making. 5th State of Australian Cities National Conference. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=591ac6e3d7f136a4dd9ea43dafb0dd5232cbd1b9

- Freestone, R., & Wheeler, A. (2015). Integrating health into town planning: A history. In The Routledge handbook of planning for health and well-being (pp. 17–36). Routledge.

- Golder, S., & Graham, H. (2024). Social media engagement in health and climate change: an exploratory analysis of Twitter. Environmental Research Health, 2. https://doi.org/10.1088/2752-5309/ad22ea

- Greater London Authority (GLA) (2025). LONDON-WIDE ULTRA LOW EMISSION ZONE – ONE YEAR REPORT. https://content.tfl.gov.uk/london-wide-ulez-one-year-report.pdf

- Neufeldt, J. (2024). How Media Framing Shapes Opinion of Environmental Policy: The Case of ULEZ. The Cambridge Journal of Climate Research, 1(2), 1–21.

- Perry, H., Heawood, J., Kapetanovic, H., Katwala, J., Knight, S., Malki, N., Mitchel, H. (2024). Driving Disinformation: Democratic Deficits, Disinformation and Low Traffic Neighbourhoods – a portrait of policy failure. Demos (May 2024).

- Quality of Life Foundation (QOLF) (2024). A Quality of Life Code of Practice For effective community consultation and engagement in development, planning and design.

- https://www.qolf.org/wp-content/uploads/Final_COP_141124-1.pdf

- Samantray, A., & Pin, P. (2019). Credibility of climate change denial in social media. Palgrave Communications, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0344-4

- Sleigh, J., & Vayena, E. (2021). Public engagement with health data governance: the role of visuality. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00826-6

- Sport England. (2023). Active Design (pp. 1–102). https://sportengland-production-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-05/Document%201%20-%20Active%20Design%20FINAL%20-%20May%202023.pdf?VersionId=8r2r2fz4cAR7cgXcuhgkDC6g4egV3bKH

- Transport For London (TfL)(2023). Why Do We Have a ULEZ? Transport for London. https://tfl.gov.uk/modes/driving/ultra-low-emission-zone/why-we-have-ulez

- TRUUD (2023). Valuing the “external” social costs of unhealthy urban development (pp. 1–3). https://truud.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Valuing-the-external-social-costs-of-unhealthy-urban-developments-1.pdf

- TRUUD (2024a). ‘Using lay knowledge to transform understanding of links between the built environment and health’. TRUUD Intervention Briefing, January 2024.

- https://bpb-eu-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.bristol.ac.uk/dist/e/1256/files/2024/01/Using-lay-knowledge-1.pdf

- TRUUD (2024b). ‘Joining up government for public health’. TRUUD policy briefing. September 2024. https://bpb-eu-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.bristol.ac.uk/dist/e/1256/files/2024/09/Joining-up-government-for-public-health.pdf

- TRUUD (2025). Changing decisions upstream with TRUUD. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T6zbJYKUAwE

- Open University (2025). ‘Achieving Public Dialogue: Public consultation vs public engagement’. Accessed 17/9/25: Achieving public dialogue: 3.2 Public consultation vs public engagement | OpenLearn – Open University

- Walker, I., & Brömmelstroet, M. (2025). Why do cars get a free ride? The social-ecological roots of motonormativity. Global Environmental Change, 91, 102980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2025.102980

- Walker, I., Tapp, A., & Davis, A. (2023). Motonormativity: how social norms hide a major public health hazard. International Journal of Environment and Health, 11(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijenvh.2023.135446

- Wang, X., Fang, B., Zhang, H., & Wang, X. (2020). Predicting the security threats on the spreading of rumor, false information of Facebook content based on the principle of sociology. Computer Communications, 150, 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2019.11.042

- White, C. C. (2022). Understanding active travel as a public health issue in Greater Manchester: A figurational sociology study [Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Chester]. In Openrepository.com. https://chesterrep.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10034/627968/CW%20PhD%20Final%20Document%20%28with%20modifications%2001.08%29.pdf?sequence=1

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2025). World Report on Social Determinants of Health Equity. Who.int. https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/equity-and-health/world-report-on-social-determinants-of-health-equity

Funding statement

Our partners

Funding statement

This work was supported by the UK Prevention Research Partnership (award reference: MR/5037586/1), which is funded by the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Health and Social Care Research and Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Natural Environment Research Council, Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), The Health Foundation and Wellcome.

Our partners

v2.23