2. Low Traffic Neighbourhoods

Traffic and street improvement schemes range in scale and type. Drawing on the example of Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) this section examines how these schemes have been introduced to date and current challenges, summarising some of the lessons to be learnt.

2.1 BACKGROUND

Purpose and benefits

Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) – also known as Active Travel Neighbourhoods, Quiet Neighbourhoods, and Liveable Neighbourhoods – are area-wide traffic management initiatives aimed at reducing pollution and the dominance of motor traffic in residential areas (DfT, 2024). They are being introduced across the UK for their range of physical and mental health benefits.

- Reduced air and noise pollution from traffic

- Improved road safety by management of traffic speeds and volumes

- Promotion of active modes of travel through creation of greater space and safety

- Reduction of pollution and provision of shade through enhanced green infrastructure

- Facilitation of feelings of connectivity to space, neighbours and local amenities

For more information on LTNs see: Borowska- Stefańska et al, 2023 ; Laverty et al, 2021; Mason, 2021; Aldred and Goodman, 2020; DfT, 2020:9; Hoogerbrugge and Burger, 2017.

Kingston LTN (Connecting

Sheffield, 2021) ▶

◀ Child playing in a LTN area

Changes introduced through LTNs

Features of each particular scheme vary, but can include:

- ‘modal filters’ that limit vehicular access and/or filter traffic through physical barriers or ‘bus gates’ which allow only buses, emergency vehicles and cycles through and can be monitored by cameras, triggering penalty notices for any breaches

- speed limit changes

- widening of pavements

- provision of safer pedestrian crossings

- extension and improvement of cycling and pedestrian pathways

- provision of seating and places to rest (e.g. Parklets, pictured right)

- introduction of bike hangars and storage

- improved green infrastructure.

Many of the changes introduced are not exclusive/ unique to LTNs and have been tested and implemented successfully as stand-alone interventions in numerous UK settings. Thousands of modal filters already exist, for example, where traffic is reduced, and School Streets, where filtering is used at set times of the day to reduce pollution and improve road safety for children entering/ leaving school, are already widespread.

▼ Keynsham Parklet (Meristem Design, 2025)

Traffic filters on Strathleven Road, Brixton Hill (Lambeth Council, 2025) ▲

Area suitability

It has been recommended that LTNs are composed of a group of streets that are within a 15 minute walk of key amenities and transport services (Jacobs Ltd, 2020). This is to ensure that most local residents are able to maintain their access to key services without needing to rely on car transport.

2.2 GREY LITERATURE REVIEW

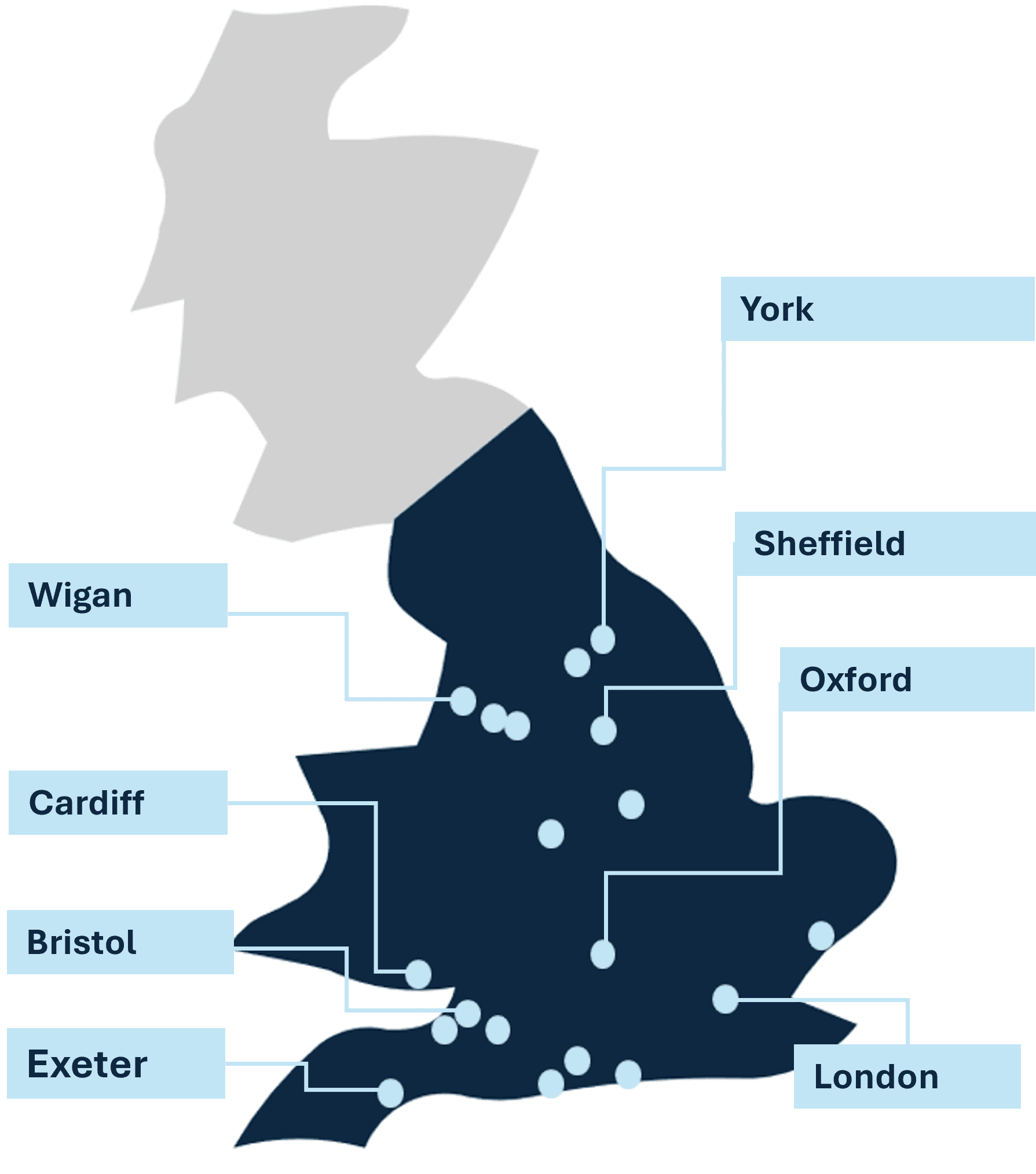

To synthesise learning from the implementation of LTNs to date, and implications for approaches to public engagement, we conducted a grey literature review of 44 LTNs across England and Wales to examine how they were implemented, have progressed and have been received locally. We reviewed any publicly available information on individual schemes and also examined learning from pre-existing LTN reviews (DfT, 2024; Perry et al., 2024). We also monitored media reporting of LTNs during the course of our work (January – July 2025).

As there is currently no single data base of LTNs in the UK, online searches to identify the schemes had to be conducted using key words of UK cities / local authorities and Low Traffic Neighbourhoods and name variants (e.g. ‘Active Travel Neighbourhood’ ; ‘Liveable Neighbourhood’). Varying detail was available for each LTN, depending on what had been published by the local authority in question. No systematic public reporting of LTNs was identified. There has been mapping of LTN projects in London, but this has not been carried out for the UK as a whole. Equally, mapping of similar features across the UK has been provided by CycleStreets Network, but this does not identify LTNs by project boundary and includes errors where road use has become outdated. This lack of consistent information and data on LTNs across different sites can be seen to impede understanding and learning about these interventions.

▲ Map of UK with researched LTN locations highlighted.

Area selection

There are two ways in which LTN areas are selected:

- By the relevant local authority. This is the most common approach and is often based on traffic and pollution data, as well as other considerations such as socio-demographic context and proximity to local amenities. Public acceptance of this external selection process inevitably depends on how the scheme is introduced and public engagement is conducted.

- By residents. A less common approach, but that used in Bath and North East Somerset (B&NES), was where the local authority received 48 applications for Liveable Neighbourhoods, before prioritising 15 for implementation (B&NES, 2024; 2025).

LTN boundaries are often determined by main roads to which traffic is redirected from residential roads which are not designed to accommodate heavier traffic volumes (see image).

Area scale

Schemes range in size from a handful of streets (see, for example, B&NES Liveable Neighbourhoods) to larger areas spanning sections of multiple electoral wards within a city (see Bristol Liveable Neighbourhoods). Scale and ambition can often be related to funding sources and local-level policies and visions.

History of Low Traffic Neighbourhoods in the UK

LTNs were first introduced in the UK in 2020 during the Covid pandemic, as national policy under an Emergency Active Travel fund. Their initial aim was to enable social distancing, reduce air pollution and encourage active travel. Post-Covid a range of local and regional initiatives were promoted to create healthier, more inclusive cities, reduce car travel and encourage people to choose to walk, cycle and use public transport.

No standard approach to the schemes was mandated; responsibility was delegated to the local authority trialling and implementing the schemes. This historical approach has been criticised for the inconsistent way that national policy was presented and how responsibility was shifted to local government with limited guidelines (Perry et al., 2024).

Following wavering national government support under the Conservative government, a Department of Transport review (2024) was commissioned. This confirmed the value of LTNs but also highlighted how schemes should have clear aims and objectives when introduced to the public, based on evidence to support their implementation.

Evidence of impact

As LTN interventions are relatively new, comprehensive, longitudinal data on their impact on public health is still lacking. Existing impact data from individual schemes are, however, compelling. For example:

- after LTNs were introduced in Waltham Forest motor traffic within the affected neighbourhoods decreased by 49.6%, while boundary traffic increased only marginally (Aldred and Goodman, 2020)

- the Department for Transport review (2024), drawing on four case study sites, found that LTNs had made a difference to both air quality and active travel

- new evidence continues to emerge regarding the positive benefits of LTNs on safety (Furlong et al., 2025).

While all impact data are highly context-specific they indicate positive outcomes, with the 2024 DfT review confirming their value and supporting their further implementation.

Timescales

From the information identified through our review LTNs typically take between 2-5 years to introduce, from earliest public engagement to final formal consultation and decision about implementation.

They operate initially as a trial implemented as an Experimental Traffic Order (ETRO) – a temporary road use regulation which lasts for a minimum of six months to a current maximum of 18 months (B&NES, 2025). Following formal consultation after the ETRO, a decision is made whether the LTN becomes permanent, and if this is the case then it is implemented as a Traffic Regulation Order (TRO). Timelines for LTNs already in process were not always transparent in the publicly available documents reviewed, including final consultation outcome and whether the initiative had been made permanent.

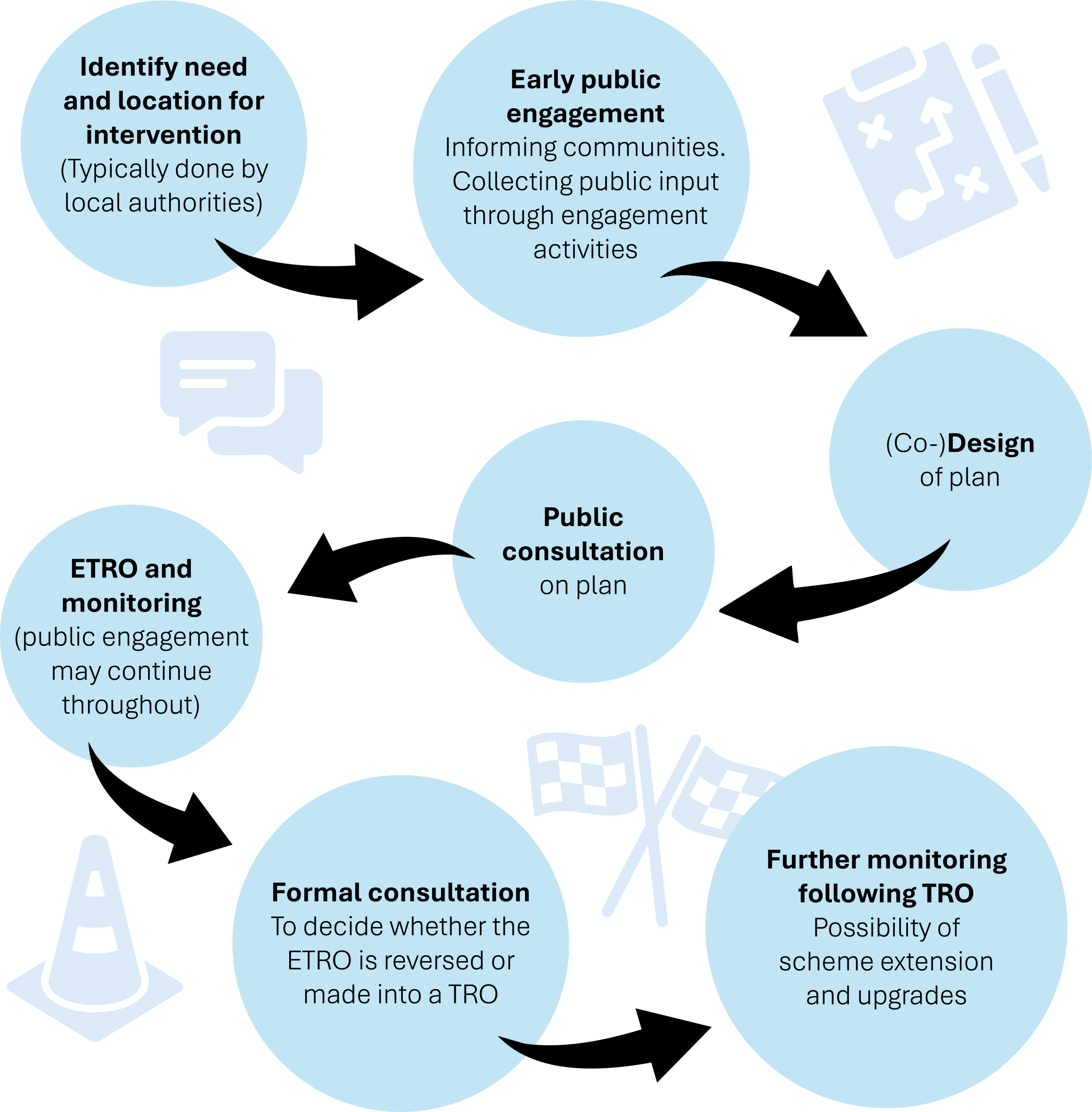

Public engagement

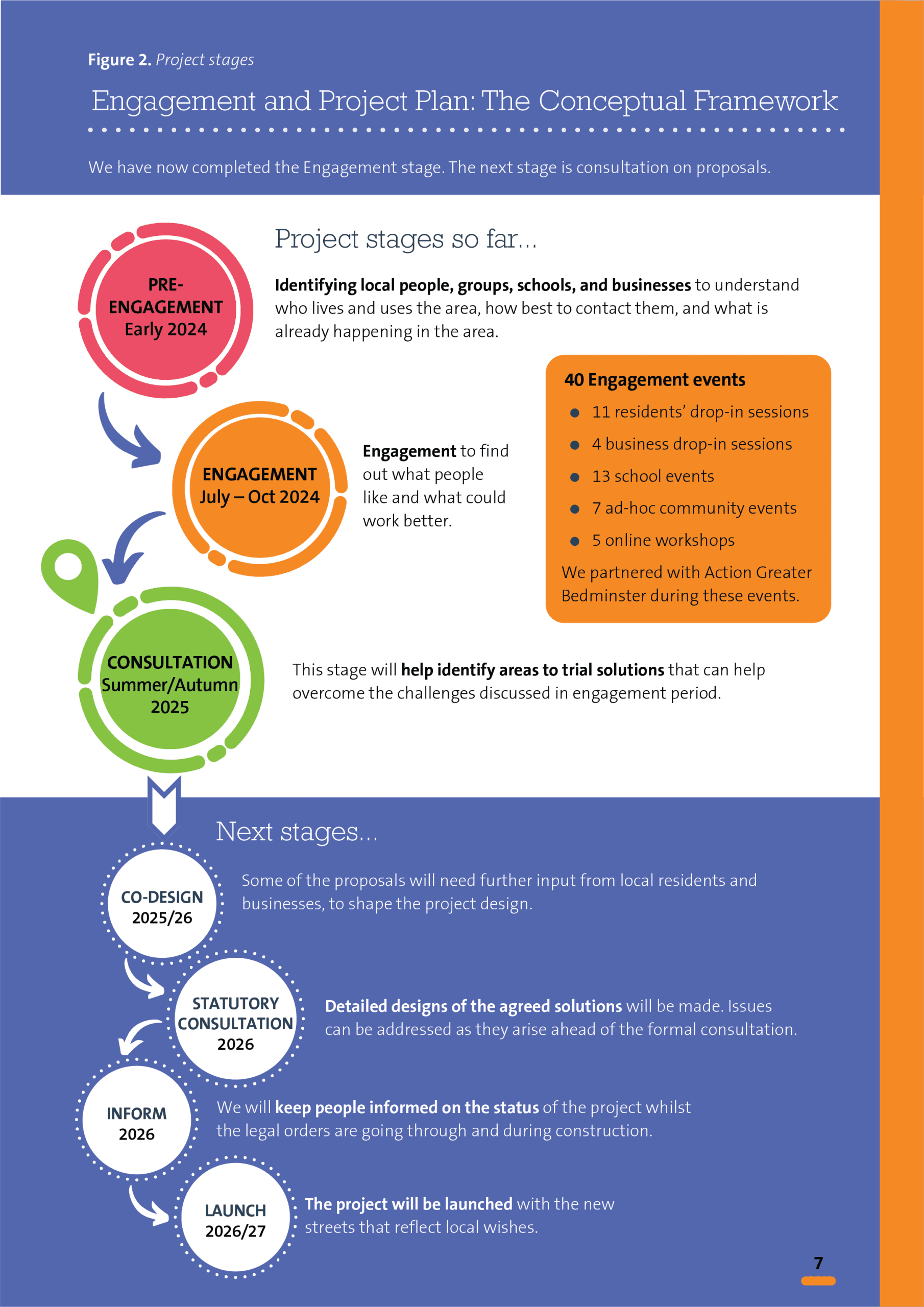

Public engagement is a necessary element in multiple stages of LTN introduction and delivery. Engagement aims to reach a range of stakeholders including local residents and the wider publics using the area, local businesses, organisations, as well as emergency services. It is conducted via a range of methods including mail-outs to residents, posters, local authority websites, online and face-to-face workshops and online engagement fora. It is a staged process (see image).

▲ Public engagement for Low Traffic

Neighbourhood delivery: typical timeline

The fragmented nature of available information on LTNs presents an obstacle to learning from prior successes and failures in public engagement. Yet drawing lessons from prior experience is essential (White, 2022). Sharing of good practice case studies is urgently required. Previous reviews, drawing on selected case studies, highlighted how certain factors impacted the acceptability of certain schemes.

- Combined failures of the local information eco system* and local government understanding of communities (Perry et al., 2024). These problems are described as creating the “fertile ground” on which disinformation thrives (Ibid: 6).

- Unclear communication of the rationale for LTN schemes (LGA 2021; Perry et al., 2024; Dft 2024) and where a narrative was poorly presented activists stepped in and seized it (LGA 2021; Perry et al., 2024).

- Poor involvement of the public in early stages decision-making whereby people feel poorly consulted (DfT, 2024).

It is noteworthy that most people in the four LTNs surveyed in depth for the DfT review (2024) were either unaware of or undecided about schemes in their area. This suggests vast scope for improved communication and engagement with the public.

*local information eco system: a network of institutions, collaborations and people on which a specific community relies on for local news, information and engagement (Perry et al., 2024: 15)

The DfT review recommends general methods for good practice engagement, including mass mail-outs, in-person and online engagement. Yet no guidance is provided on the advised content and focus of early engagement activities whereby the schemes are first introduced. This responsibility lies with the relevant local authority. This area of work is the particular interest and focus of this toolkit.

2.3 KEY ISSUES IDENTIFIED

- Under-developed links to public health evidence. The brief rationales used to introduce LTN schemes can often be ambiguous and confusing and often fail to explicitly communicate the population health risks which are being addressed.

- Exploration of local knowledge as a starting point for intervention design is limited by the lines and methods of enquiry pursued

- Methods of engagement with diverse publics and its influence on outcomes

“Public understanding plays a crucial role in the acceptance and implementation of scientific knowledge’

Vinatier et al, 2024:1

- Under-developed links to health evidence

‘Health’ and ‘healthier streets’ were referred to in the descriptions of the LTN schemes whose public-facing information we reviewed. Few cases were found where current health harms were specified and the important contribution to the prevention of non-communicable disease that a scheme could bring highlighted. Typically, stated rationale/s focused on a need to reduce (air) pollution, increase climate resilience, and encourage active travel, often presented as confusing composite statements. Notably:

- Explicit linkages between air pollution and non-communicable diseases such as asthma, lung, heart conditions and dementia were very rarely detailed, underplaying the preventive potential of LTNs

- ‘Health; was largely linked to individual behaviour (physical activity) rather than broader built environment determinants

- Mental health was often referred to as ‘wellbeing’ without defining mental health impacts of the built environment and the importance of countering measures

- Planetary and population health were poorly distinguished.

‘The LTN will reduce the level of harmful emissions from motorised vehicles driving through the area, help people stay physically active and healthy, and encourage a shift to more sustainable modes of transport.’

Extract from Newham and Waltham Forest Low Traffic Neighbourhood Consultation Leaflet

‘This work supports a wider programme of… taking emergency action to help people of all ages to walk and cycle safely as part of the council’s ‘safe streets, save lives’ campaign and further supporting greener, healthier, safer neighbourhoods for Leeds residents.’

Extract from Hyde Park Active Travel Neighbourhood Web Announcement

▲ ‘Modal filters’, East Bristol Liveable Neighbourhood – Photo: J. White

- Exploration of local knowledge as a starting point for intervention design limited by the lines and methods of enquiry pursued.

Early understanding of a local area enables existing demographics, the presence of different communities and cultural and social assets, existing infrastructural and service access issues, as well as any tensions and divisions to be grasped prior to introducing new ideas about change.

A common approach to engagement observed from information available online was the use of digital maps to enable public input related to proposed LTN areas. This involves pinning comments on a webpage using digital tools and on physical maps during parallel in-person sessions. Broad questions were asked such as what residents like/do not like/would like to change in the defined LTN area.

This starting point for concerted exchanges has limitations. Firstly, it risks raising expectations. There are risks of damaging trust with this approach unless the aims and parameters of a proposed scheme and the role and scope of public contributions in designing change are clearly understood.

This line of enquiry can also limit broader early explorations which enable sharing of lay knowledge. Alternative approaches might include probing both historic and present sense of place related to specific areas, street-based and travel behaviours and the factors influencing these, and the use and sharing of space by different publics/ communities and its impacts.

Map of Brixton Hill LTN boundary and comments showing community comments on the local area ▶

Such collection of lay knowledge, together with the use of different forms of health evidence and other data on travel patterns etc, can provide an entrypoint for introducing early conversations about change even prior to demarcating an area for an intervention. Unless underlying public health evidence (be this at national or local level or both) informs this process then collecting such information focuses on public perspectives about certain issues, which may not be founded on full understanding of public health impacts of the built environment. Air and noise pollution have significant impacts which affected populations may not be aware of, for example. Integrating both the quantitative and qualitative background evidence in these early stages is important.

It should be noted that any over-reliance on the provision and collection of information online and digital mapping methods pose a barrier to inclusive engagement practice. Poor digital access and civic digital literacy continues to exclude many already marginalised groups from engaging in web-based engagement (Perry et al., 2024).

A previous review of digital engagement tools by the TRUUD Public Advisory Group highlighted some of these issues.

Map of Brixton Hill LTN boundary and comments showing community comments on the local area ▼

- Engagement with diverse publics

From the information reviewed, gaps were identified in some instances in reporting on how reaching diverse publics were both provided with accessible information and included in engagement activities. This included gender, mix of ages, the involvement of different cultural groups and communities, and those with different disability status.

One recognised good practice approach identified was where communications were made available in the diversity of languages commonly spoken in the local settings so that all residents could access information about the proposed scheme. For example, in Edmorton Green Quieter Neighbourhood (Enfield, London) resident letters were provided in Turkish, Somali, Polish, Greek, Gujarati, Albanian, Romanian, and Bulgarian (Enfield Council, 2023).

Plain English communication which avoids jargon and overly technical terms is, of course, a cornerstone of collaborating effectively with all publics literate in English. A wider question is how diverse groups are enabled to not only understand the ideas and evidence behind new initiatives, but also to participate in engagement discussions and remain informed beyond initial information through mass mailing, such as about engagement outcomes, consultation timelines etc. These include not only non-English speakers and those with English as a second language, but also those who are not used to dealing with large amounts of information, and those who do not use digital communication. There is significant scope for sharing learning in this area and developing best practice approaches, and defining strategies for including the public in the design of appropriate communication materials.

2.4 TOWARDS IMPROVED ENGAGEMENT*

To address the issues identified, attention needs to be paid to the following:

1) how the scheme is introduced

2) communication of rationale: use of health evidence

3) ensuring breadth of engagement

4) transparency of process

*These suggestions combine the learning already presented, combined with engagement good practice as outlined in multiple sources (see QoLF 2024)

Introduction of the LTN

- Avoid initially introducing LTNs in the most underserved areas of a city/urban location where trust in government may be low, there may be pressing priorities and needs in multiple sectors amongst the most vulnerable, and the proposal of change may feel like a burden unless it is carefully managed.

- While introducing LTNs in the most underserved areas may be vital, given these areas may be most affected by the health impacts which LTNs seek to address, any such initiative needs to involve recognition of and meaningful response to wider issues of deprivation and neglect to build trust. Although local governmental and local authority departments and roles and responsibilities are distinguishable to those working within them, to many publics ‘the Council’ is one entity (Perry et al., 2024).

- Introduce LTNs across a small area, spanning several streets, and where successful, gradually expand to a wider area. This makes early, comprehensive public engagement more manageable (NB. this option may not always be feasible, depending on funding sources and other infrastructural factors influencing LTN delivery).

- Make efforts to explore and draw on lay knowledge early on. This includes investigating current sense of place related to a given area, street-based behaviours and the use and sharing of space by different publics/ communities.

- Lay knowledge exploration can include collecting stories about links between the built environment and health in the local area through film or other forms of evidence collection. See our learning in this area in Section 6 Resources where we share lived experience films.

- Acknowledge and facilitate/signpost to support around local areas of concern which may lie outside the remit of any LTN.

- If the LTN is part of planned city-wide change, flag this. This reduces the sense that a specific area/community is being singled out.

- Share evidence on how many of the features of LTNs are not new, and similar initiatives have already been carried out successfully – where possible including examples of interventions close to the proposed project area.

- Be explicit that any scheme introduced is a trial for testing outcomes and cannot be made permanent until after the pilot and formal consultations with the public. Describe the process in detail, including how you intend to monitor and evaluate the scheme following its introduction as a trial.

- (Re-)Consider the scheme name. ‘Low Traffic Neighbourhoods’ and related terms have become tainted in public perception in some settings. Involve the public/community organisations in deciding an acceptable descriptor.

Communication of rationale: use of health evidence

-

Present the public health rationale underpinning the scheme.

- Show that current traffic volumes and flow are causing harm, which underscores the need for change. This promotes equity of access to information and enables different ways of thinking about and understanding how the built environment affects and physical and mental health. This involves challenging motornormativity.

- A health and people focus can demonstrate the need for and collective value and benefits of change. This can move public perceptions of LTNs away from that of an externally-imposed transport management intervention.

- Consider what kinds of health data are most relevant to the scheme context and your different audiences. Incorporate framing principles so information is designed to communicate clearly with and appeal to the public. For learning on how to frame health-focused messaging see Section 3. For learning on the introduction and presentation of health data with the public see Section 4.

What kinds of health data are missing?

Air pollution from traffic is related to multiple health issues including the development of asthma, and lung conditions (including cancer), heart attacks and cardiovascular issues, strokes, dementia and cognitive decline.

Children are particularly at risk as their bodies are still developing and they breathe faster, meaning they inhale more pollution. Pollution exposure amongst pregnant women can also affect birthweight.

Noise pollution from traffic can disrupt sleep causing fatigue, stress, anxiety, which then lead to an increased risk of diabetes, heart disease, and strokes. Noise pollution can also be isolating for those with hearing impairments.

There is growing evidence of the links between streets and health, including emergent data on cognitive impacts such as dementia (WHO, 2023; TfL, 2023). Urgent action is required to reduce harms.

Ensuring breadth of engagement

Ensuring breadth of engagement

- Reaching different cultural groups, particularly those typically under-represented, is vital, as is including those who are disabled or have visual or aural impairments and particular experiences of traffic and street spaces. In addition, engaging with both younger and older people who face particular health risks related to pollution and may be less likely to drive is important. These diverse groups will have particular perspectives on infrastructural improvements and ‘active travel’, as well as public transport options. Engaging with such groups should be strategic, depending on the information sources they use, their access to digital media, and their availability for in-person meetings. Dedicated officers working consistently with a range of community groups is a proven approach.

- Digital communication and engagement should never be considered a substitute for mail-outs, posters and face-to-face engagement activities, given the ongoing digital divide.

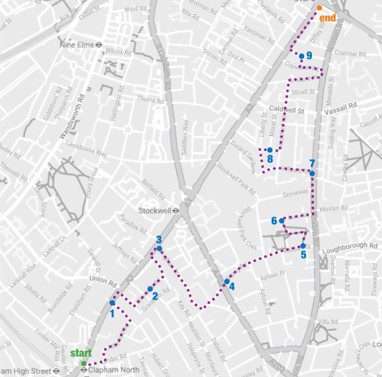

- Developing understanding of local experiences of space at different times of the day and night can feed into early design. For example, women’s experience of safety. For Slade Gardens LTN (Lambeth), a walking workshop was held at night to identify public space concerns for women and ways of addressing these.

▼ Route of Women and Girls Evening Walk through Slade and Stockwell Gardens LTN (Lambeth Council 2024)

Groups that experience disproportionate health outcomes and inequalities should have disproportionate efforts made to be engaged with – Liljas et al., 2017

Transparency of process

- Detailed monitoring of and reporting on engagement sessions, assessing to what extent those who contributed represent the diverse range of publics which co-exist and identifying and addressing gaps is essential. Creating and disseminating engagement session summaries describing what was discussed and produced and how the information is being used establishes reciprocity. Plain English versions (with community representative input to ensure accessibility) are key to avoid jargon and misunderstanding.

- An important distinction can be made between the breadth and depth of engagement. ‘Breadth’ refers to the diversity of publics included in the engagement process and the heterogeneity of voices included (see 3 in this section), ‘depth’ can be considered the demonstrable contribution made by the public through meaningful involvement in the decision-making process.

- For the public to be meaningfully involved they must understand the decision-making process. This needs to be explained in accessible language, with versions in locally relevant languages as appropriate. Shorter, simplified versions or short videos can explain complex detail/longer denser documents in plain language. If there are funding sources requiring certain time frames and actions related to interventions being explicit about this context supports transparency.

- Maintaining a website and wider online presence through social media as well as paper versions describing what stage the project is at and what can be expected to follow enables the public to understand how they can be involved. Clarity of goals and process and careful framing, disseminated through the local information eco-system, using multiple media, is essential, given there may mis-/disinformation circulating online.

Example of a project timeline, South Bristol Liveable Neighbourhoods Engagement Report (BCC, 2025) ▶

- Regular summary updates should be provided (ideally every 3-5 months). It is crucial not to go quiet so that the public feel updated and to avoid misconceptions and a vacuum where mis/dis-information can circulate. Providing one responsive point of contact facilitates trust.

- A reflexive record of learning enables the public and others to understand what elements have been successful and why.

Example of a project timeline, South Bristol Liveable Neighbourhoods Engagement Report (BCC, 2025) ▶

2.5 PUBLIC OPPOSITION

Some LTNs have become mired in controversy, facing active local opposition, including vandalism (Withington LTN), protests (Oxford LTN, East Bristol Liveable Neighbourhood), and legal challenges (West Dulwich LTN). Much of the opposition expressed around specific LTNs has related to specific, localised concerns around:

- Risks of possible displaced traffic and associated pollution and congestion (Mason, 2021; Pritchett et al, 2024)

- Implementation in areas with insufficient public transport

- Potential impacts on local businesses

- Failure to explicitly recognise and accommodate the needs of the most vulnerable hence schemes potentially exacerbating existing inequalities

In addition, wider general support of /opposition to the schemes has led to polarising discussions in the press and on social media. While a “silent majority” is often claimed on different sides, each scheme can only be fully understood in its particular context (LGA 2021).

Local policy-makers and funding sources are shaping the rollout of LTNs in terms of pace and scale. But in every case how the public was involved in the initial introduction and development of each LTNs and how their views were considered is of critical relevance and importance to outcomes.

Opposition can lead to the pausing, alteration or reversal of LTNs. In the case of Heavitree and Whipton LTN (in Exeter), for example, some scheme elements were removed and others retained. The most striking example of opposition to date is that of West Dulwich LTN. In this case West Dulwich Action Group (WDAG) was supported by a community fundraiser of over £50,000 which enabled the group to take Lambeth Council to court (Low, 2025).

The court case led to a High Court ruling in May 2025 that Lambeth Council’s consultation on the introduction of the scheme had failed in its lack of consideration of local concerns in decision-making. This resulted in the removal of the scheme.

Delays in, or abandonment of, initiatives aimed at preventing non-communicable diseases bring inevitable costs, not least the delayed opportunity for the collaborative improvement of the health of local populations. The costs of public opposition to LTNs, as well as media/social media representations of conflict and division around such cases, are also immeasurable in terms of the overall reputation of LTNs, damage to relationships between the public and those responsible for delivering them and the overall negative impact on public trust, which is not easily recovered.

Opposition and associated delays or reversals also bear substantial costs to the local government or combined authority which have invested resources in introducing LTNs. The experience in West Dulwich highlights the importance of inclusive and transparent engagement processes.

Section 2: Key points and learning

- Low traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs) are traffic and street improvement schemes intended to enhance population health.When implemented effectively they have proven benefits.

- Communication and public engagement approaches related to the schemes are critical factors affecting their acceptance and success. Flawed approaches provide “fertile terrain” for the circulation of mis- and dis-information.

- Current national government guidance on public engagement for LTNs provides limited detail on advised approaches to early engagement.

- The fragmented nature of available information reporting on successes and failures in public engagement around LTNs inhibits learning about good practice.

- Addressing current challenges to the introduction and implementation of LTNs is essential to promote the prevention of non-communicable diseases.

Learning

- The inclusion of public health data and evidence in the communication of the rationale for LTNs can improve public understanding of the rationale for these schemes and ensure equitable access to information as context to discussions around change.

- Public engagement can be enhanced by gaining early in-depth understanding of the local context and drawing on lay knowledge before the specificities of any scheme have been defined, and by ensuring a diverse range of people are reached through multiple approaches and comprehensive use of local information channels.

- Transparency of process, including the role of the public in decision-making is essential.

- Sharing of good practice case studies around public engagement for LTNs would be instructive. Learning from the rare cases where communities were invited to volunteer for an LTN in their area could provide important new insight.

REFERENCES

- Aldred, R., & Goodman, A. (2020). Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, Car Use, and Active Travel: Evidence from the People and Places Survey of Outer London Active Travel Interventions. Transport Findings. https://doi.org/10.32866/001c.17128

- Bath and North East Somerset Council (B&NES). (2024). Approach to developing Liveable Neighbourhoods | Bath and North East Somerset Council. Bathnes.gov.uk. https://www.bathnes.gov.uk/approach-developing-liveable-neighbourhoods

- Bath and North East Somerset Council (B&NES). (2025). Experimental Traffic Regulation Orders (ETROs) | Bath and North East Somerset Council. Bathnes.gov.uk. https://www.bathnes.gov.uk/experimental-traffic-regulation-orders-etros

- Borowska-Stefańska, M., Felcyn, J., Gałuszka, M., Kowalski, M., Majchrowska, A., & Wiśniewski, S. (2023). Effects of speed limits introduced to curb road noise on the performance of the urban transport system. Journal of Transport & Health, 30, 101592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2023.101592

- Bristol City Council (BCC). (2025). South Bristol Liveable Neighbourhoods Engagement Report, May 2025. https://www.bristol.gov.uk/files/ask-bristol/9800-south-bristol-liveable-neighbourhood-engagement-report/file

- City of York . (2021). THE GROVES LOW TRAFFIC NEIGHBOURHOOD, YORK. https://www.york.gov.uk/downloads/file/6675/the-groves-low-traffic-neighbourhood-trial-stage-3-road-safety-audit

- Cycle Streets. (2025). LTNs and modal filters map. Lowtrafficneighbourhoods.org. https://www.lowtrafficneighbourhoods.org/map/ltns/#11.01/51.49/-0.0935

- Department for Transport. (2020). Gear Change A bold vision for cycling and walking. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5f1f59458fa8f53d39c0def9/gear-change-a-bold-vision-for-cycling-and-walking.pdf

- Department for Transport. (2024). Implementing low traffic neighbourhoods. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/implementing-low-traffic-neighbourhoods/implementing-low-traffic-neighbourhoods

- Enfield Council. (2023). Edmonton Green Quieter Neighbourhood | Let’s Talk Enfield. Letstalk.enfield.gov.uk. https://letstalk.enfield.gov.uk/edmontongreenqn

- Healthy Streets. (2022). Mapping London Low Traffic Neighbourhood schemes and where we’re at. Healthy Streets Scorecard. https://www.healthystreetsscorecard.london/ltn-low-traffic-neighbourhood-schemes-mapping/

- Hoogerbrugge, M. M., & Burger, M. J. (2018). Neighborhood-Based social capital and life satisfaction: the case of Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Urban Geography, 39(10), 1484–1509. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1474609

- Ipsos. (2024). Low Traffic Neighbourhoods Research report. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65f400adfa18510011011787/low-traffic-neighbourhoods-research-report.pdf

- Jacobs Ltd. (2020). Bath and North East Somerset Council – Low Traffic Neighbourhood Strategy (pp. 1–66). https://www.bathnes.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2022-05/Low%20traffice%20neighbourhood%20strategy%202020.pdf.

- Lambeth Council. (2024). Slade Gardens Low Traffic Neighbourhood. Lambeth Council. https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/streets-roads-transport/low-traffic-neighbourhoods/slade-gardens-low-traffic-neighbourhood

- Laverty, A. A., Goodman, A., & Aldred, R. (2021). Low traffic neighbourhoods and population health. BMJ, 372(443), n443. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n443

- LGA (2021). ‘Stakeholder engagement in an emergency: Lessons from low-traffic neighbourhoods’. Stakeholder engagement in an emergency: Lessons from low-traffic neighbourhoods | Local Government Association

- Liljas, A. E. M., Walters, K., Jovicic, A., Iliffe, S., Manthorpe, J., Goodman, C., & Kharicha, K. (2017). Strategies to improve engagement of “hard to reach” older people in research on health promotion: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4241-8

- Living Streets. (2025). Parklets. Living Streets. https://www.livingstreets.org.uk/policy-reports-and-research/parklets/

- Low, H. (2025, May 9). West Dulwich low-traffic neighbourhood (LTN) unlawful, High Court rules. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/ckg4178plvdo

- Mason, L. (2021). Low-traffic neighbourhoods – what’s not to like? Perspectives in Public Health, 141(2), 70–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913920985998

- Pritchett, R., Bartington, S., & G Neil Thomas. (2024). Exploring expectations and lived experiences of Low Traffic Neighbourhoods in Birmingham, UK. Travel Behaviour and Society/Travel Behaviour & Society, 36, 100800–100800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2024.100800

- Sandor, A. (2021, February 14). Residents asked for “low traffic” streets. They got a neighbourhood war. The Mill. https://manchestermill.co.uk/p/residents-wanted-low-traffic-streets

- School Streets Initiative. (2025, February 16). School Streets Initiative – All the information you need. School Streets Initiative. https://schoolstreets.org.uk/

- Smorto, F. and Williams, N. (2024). Brixton Hill Experimental Traffic Scheme – EQIA. Equalities Analysis in Lambeth.

- Transport For London. (2023). Why Do We Have a ULEZ? Transport for London. https://tfl.gov.uk/modes/driving/ultra-low-emission-zone/why-we-have-ulez

- Vinatier, C., Kozula, M., Van den Eynden, V., Caquelin, L., Roubik, H., Stegeman, I., & Naudet, F. (2024). Public engagement with research reproducibility. PLoS Biology, 22(12), e3002953–e3002953. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002953

- World Health Organisation. (2023). Dementia. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

Funding statement

Our partners

Funding statement

This work was supported by the UK Prevention Research Partnership (award reference: MR/5037586/1), which is funded by the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Health and Social Care Research and Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Natural Environment Research Council, Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), The Health Foundation and Wellcome.

Our partners

v2.23