4. Public engagement ‘test event’

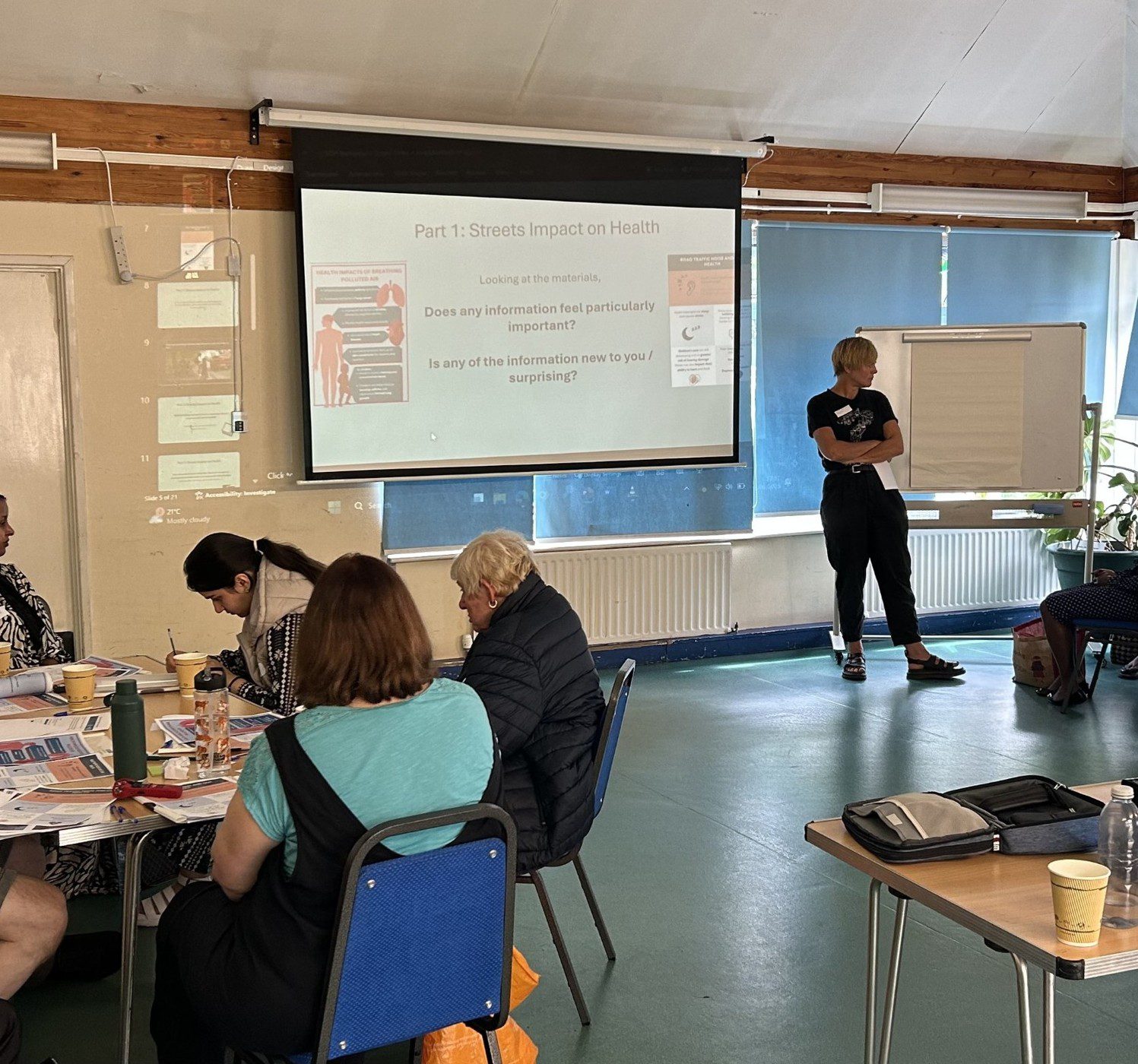

In June 2025, the TRUUD Public Involvement team ran a workshop event entitled ‘Our Streets Our Health: Imagining Change’ to test how creative engagement materials based on health evidence and framing might:

- promote understanding of the links between urban streets and health

- facilitate discussions about the need for change and begin conversations about what change should look like

- be replicated in other public engagement activities.

Event materials, activities and structure were co-designed with the TRUUD Public Advisory Group and Knowle West Media Centre

4.1 EVENT OVERVIEW AND STRUCTURE

The event explored how informing the public about relevant health evidence and inviting them to explore rationale/s for street change(s) and share experiences in a discursive setting could lead to meaningful and strategic contributions as part of early-stage engagement (see Bailey, 2010; Kwiatkowska, 2016).

A group of 18 local people were purposively recruited through a range of different community organisations across Bristol to ensure a wide mix of contributors. Participants included representation from different ethnic and cultural groups, including representatives from Black Caribbean, Asian, Muslim and White communities, and those living with physical disability and learning difficulties. We deliberately recruited a mix of ages, ranging from one participant in her early 20s to two individuals over 75 years of age.

Materials used for the event were informed by the learning set out in earlier sections of the toolkit, including:

- Two printed posters to convey evidence about pollution and health in an accessible format, with references. These were co-produced with the TRUUD Public Advisory Group to maximise accessibility. Framing of the printed materials emphasised health impacts on people.

- Lived experience of streets and pollution, including impacts on children through a documentary-style short film sharing families’ journeys to school across the city. This humanised the issues.

- A printed poster sharing some typical urban design interventions used to prevent poor health

Streets definition

A definition of streets was read out to participants as part of the introduction to the event and was also provided on a printed sheet so they could refer to it throughout the session:

“Streets are the public spaces everyone can access that connect the places we live, work, and move in and through. They include pavements, roads, the outside of buildings (shopfronts, fronts of houses), and the things people interact with such as benches, trees, crossings”

The event used the following structure. Details of and learning from each element of these are explained throughout this section.

1. Opening segment – Introduction, survey, and icebreaker

2. Sharing of air and noise pollution posters and discussion

3. Screening of short film and discussion

30-minute lunch break

4. ‘Imagining change’ – group work and discussion

5. Exit survey

All proceedings were audio-recorded (with consent).

A live illustrator was also present to capture discussions.

See Section 6.3 for copies of the materials used at the event.

4.2 OPENING SEGMENT

What happened?

After welcoming participants, we opened the event by :

- Introducing the session

- Providing a definition of streets with relevant photos to create mutual understand of the session focus

- Asking participants to fill out a short survey rating their understanding of streets and health and detailing their key concerns etc

- Asking everyone to introduce themselves through an icebreaker question: “What was something you noticed about the streets you used on your journey here today?”

The icebreaker allowed participants to get to know each other by sharing their own experience and what was important to them.

The facilitators also took part in sharing their experiences during the icebreaker, creating, less of a separation between researcher-facilitators and participants.

What was the learning?

- The survey findings and sharing through the icebreaker revealed how participants were already concerned about how streets impact health – including factors related to air and noise pollution – and their desire for change.

“Because it affects our health mentally and physically, as I use streets with my family everyday, so it makes me concerned”

Participant response to pre-event survey

Value of the icebreaker :

- Established a welcoming atmosphere, with people becoming comfortable in sharing their thoughts, and created a sense of group in which people would feel more comfortable to talk about health and their local areas

- Provided participants a space to feel listened to through being encouraged to talk about something significant to them prior to session discussions. One woman described her enjoyment at seeing a plant species growing next to the event location that represents her Caribbean family heritage – giving the group insight into local assets and how they are appreciated.

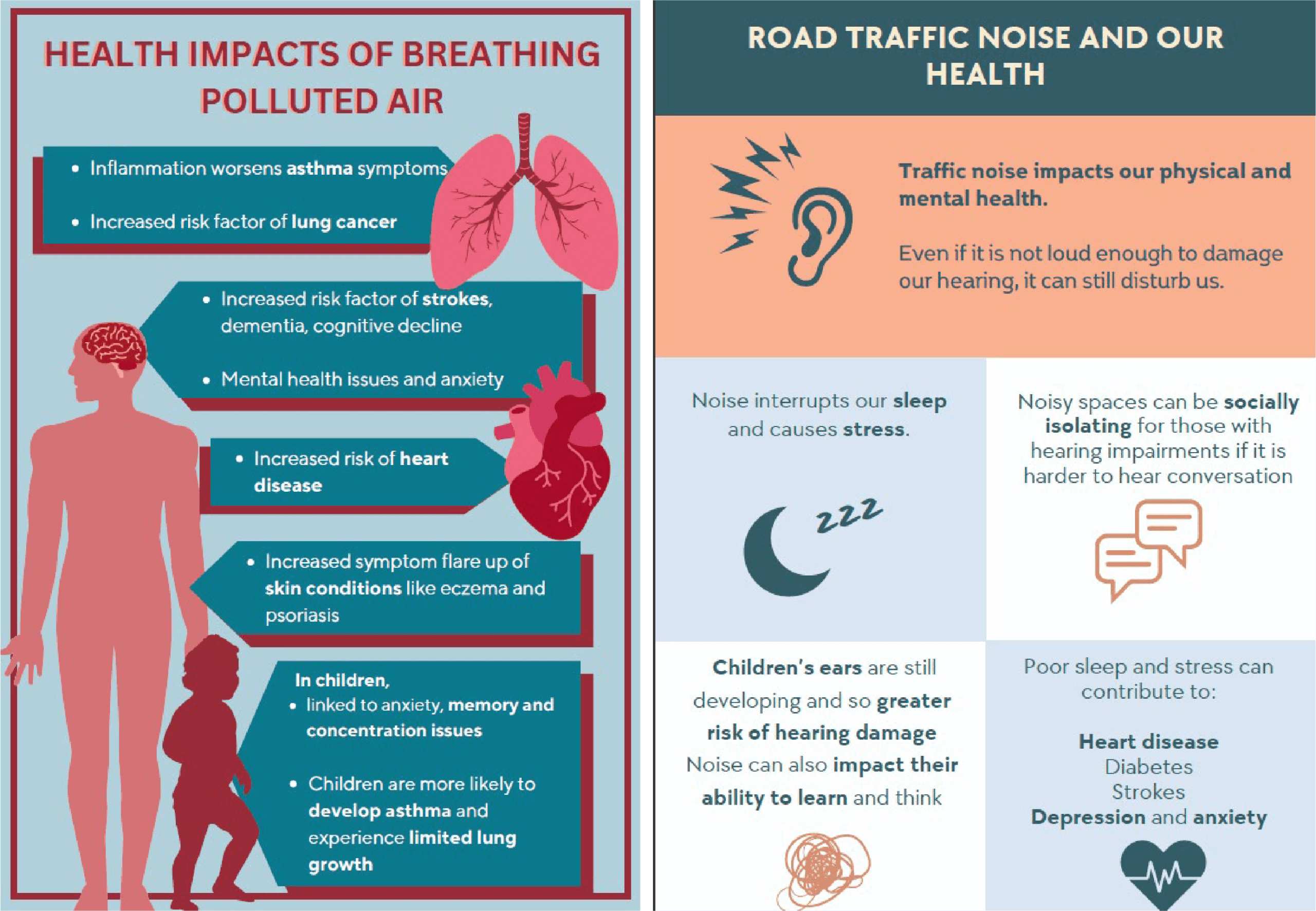

4.3 HEALTH AND POLLUTION POSTERS

What happened?

We provided printed posters for participants to discuss in small groups at a table, and then as a wider group.

One showed the health impacts of air pollution, and another of noise pollution, with data references provided on the back.

The purpose of the posters was to improve access to evidence, allowing participants to deepen their understanding, as well as to inform subsequent discussions during the event.

Posters emphasised impacts on people, instead of focusing on specific data and costs related to the NHS and government. The text explained impacts on daily activities, social and mental wellbeing as well as physical damage to the body.

Participants were asked prompt questions about whether they found any of the information surprising and/ or relatable.

Participant responses to the posters

What was the learning?

- The posters successfully conveyed the health impacts of noise and air pollution, and were effective in developing understanding beyond what participants had already known. This was reflected in discussions and the post-event survey – see 4.6).

- The posters prompted participants to relate health evidence to lived experience – particularly of asthma and sleep disturbance. This engaged people in the stories that were shared during discussions even if for some participants what was described was something they had not directly experienced themselves.

(See Appendix B for details on how these materials were produced)

4.4 LIVED EXPERIENCE FILM

What happened?

A short film was screened showing various traffic-related challenges facing three families during their journeys to school. During the film, the parents featured talked about their concerns regarding the impact of car-dominated streets on their children, including the health impacts of air pollution on their children’s asthma, and stress related to safety.

The inclusion of this film as an element of materials for the event was based on earlier learning about the value of short films in sharing lay knowledge about the multiple impacts of the built environment on health, and stimulating new understanding as well as emotional responses, through humanisation of the issue.

After the screening, participants were asked whether they found the film engaging and / or relatable, and whether the topics were well communicated by the way the families spoke about such impacts. Stills from the film were provided on a printed sheet to prompt reflections.

Participants found the film engaging. In the subsequent discussion some mentioned their own challenging experiences of the school run. Others expressed surprise and new learning at being shown the vulnerability of young children.

“Well presented film details the stress of the journey”

“I saw cars parked on pavements, and that’s really awkward for people that need to go past in a wheelchair or buggy”

Participant responses from discussions and post-event survey

What was the learning?

- Lived experience films are effective for provoking emotive responses, particularly where children are featured, and the disproportionate health impacts on this vulnerable group are evident

- Visual and audio shots of traffic are effective for conveying this issue in a relatable way – particularly for participants not regularly experiencing this issue themselves and the direct physical impact of a health-risk is not always so obvious

- Where possible films should present a narrative that demonstrates a tangible cause and effect that can be discussed, together with key take-home messages. Through personal narratives the ‘Getting to School’ film presents a multi-faceted “wicked problem” associated with historical road infrastructure, traffic and human behaviour. Careful facilitation is therefore required to focus on health impacts caused by traffic, and the scope for and necessary focus of change.

▲ Stills from the film

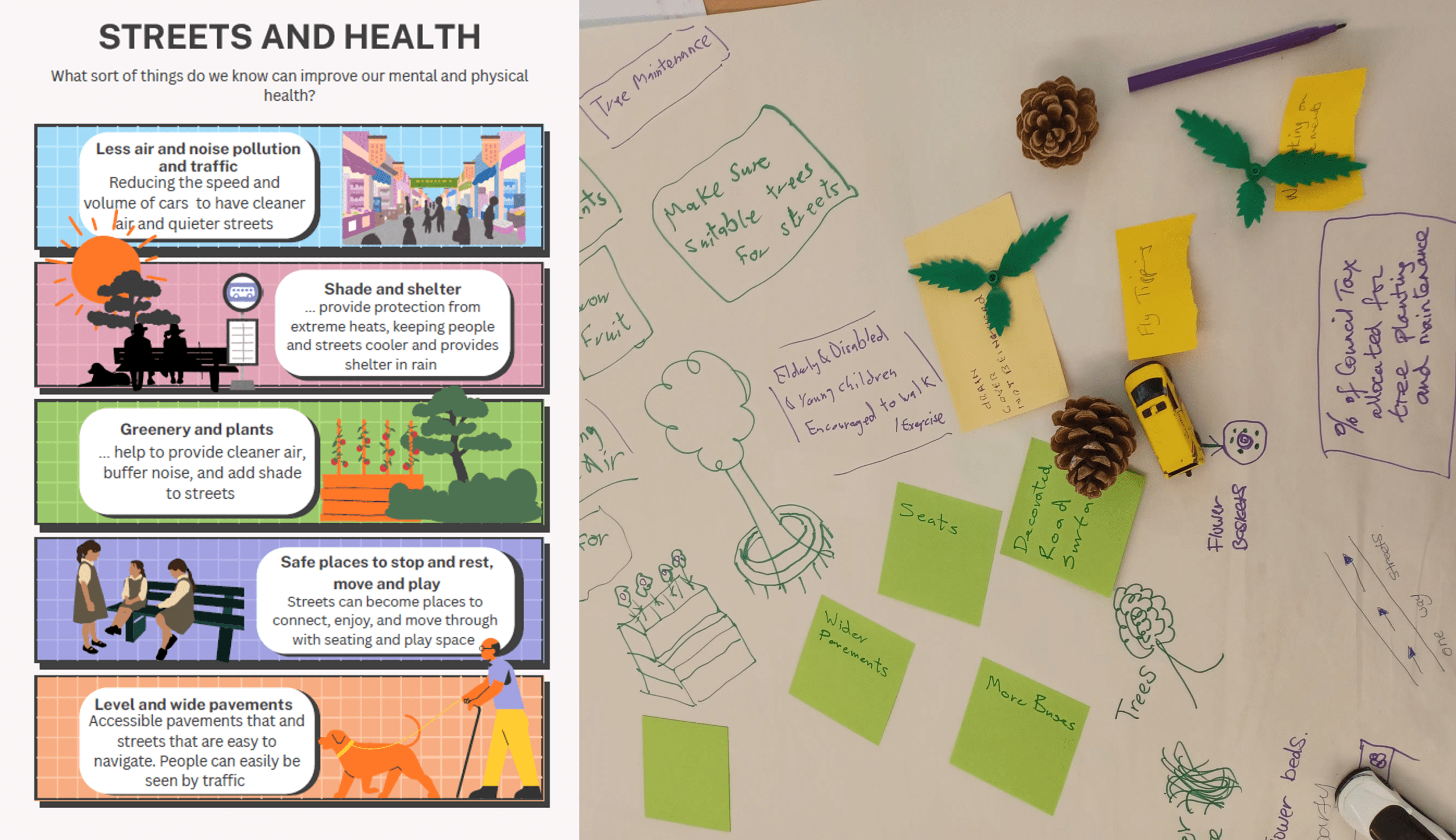

4.5 IMAGINING CHANGE

What happened?

The second half of the event was designed to see how people thought change could best be achieved to address the health risks already discussed. Participants were given A3 sheets of paper to draw and write on, as well as toys/ models to represent their ideas. During this segment, prompts were provided to encourage the groups to consider what groups of people may be particularly affected in their discussions (e.g. children, disabled people).

We also shared a poster of typical street design changes used to improve health, featuring elements such as reductions in traffic, wider pavements and improved provision of shade and their positive impacts. We asked whether these interventions seemed appropriate and how similar they were to what the groups had already come up with. This was to help share key ideas from urban design practice and literature in an accessible way and contribute to reflections about possible and tangible solutions.

As well as discussing changes to traffic volume and street infrastructure, participants were interested in talking about the enforcement of parking rules, anti-social behaviour, and cleanliness of streets and how these contributed to health risks.

“If you have the choice, you can make certain decisions to live in certain places, to not be near noise, to not be near pollution”

Participant response captured on audio

What was the learning?

- Well-informed and careful facilitation and sufficient time are required to enable discussion about how different factors are linked and keep the debate focused on constructively addressing key issues, while also acknowledging the range of concerns which might be raised about the impact of streets on people’s lives

- Becoming sensitive to local context and existing inequalities emerged as an important issue. Different participants had quite distinct experiences, with some reflecting on how they had learnt from the experiences shared that they themselves could (and had) made choices to move area, while others could not.

“(The discussion) gave me more insight on others’ experiences and ideas of how to tackle problems”

Participant responses from discussions and post-event survey

4.6 EXIT SURVEY

What happened?

At the end of the event we asked participants to complete a survey to assess whether there had been a change in their perspective/ understanding, as well as to evaluate the materials and session overall. The survey asked participants:

i) To rate their understanding of streets and health – this was repeating questions from the introductory survey at the opening of the event) to measure if/ how their perspectives had changed

ii) Their opinions on the relatability of and their engagement with the materials provided. Questions were asked about each material individually to prompt more precise answers.

iii) Whether they felt any relevant information had not been discussed / presented in the materials

iv) Feedback on the session overall, including ideas on what could be improved.

The exit survey enabled a deeper understanding of the use of the session/ materials, helping identify which aspects would be beneficial to repeat. It also gave voice to those who may have been quieter throughout the session, which is also important to consider.

“I think such community gatherings can make us think that not only us, but everyone is facing issues”

Participant response recorded in exit survey

What was the learning?

- Half of the group reported that they had learnt completely new knowledge about the impacts of streets on health. Others reported already having some underlying knowledge but learning new details. This highlights a gap in public knowledge about health and streets that should be addressed in the provision of background information and rationales for change in relation to new interventions.

- Some participants reported wanting greater discussion / presentation of: safety issues (antisocial behaviour and traffic); fear of injury from traffic of pedestrians and cyclists; the (in-)ability to enact choice in determining which street-based health-risk factors you are exposed to – such as whether you can afford to move to a different area. This demonstrates the importance of being prepared to facilitate deliberative discussion around key local issues, and consider how to address these in conversations around intervention engagement / design generally. It also highlights the importance of recognising inequalities and disproportionate impacts and introducing these in early discussions.

The survey helped clarify what worked well, and provided suggestions for what could work better.

- Participants reported finding the event stimulating, and that discussions had put their own experience into perspective.

- Findings affirmed the value of engaging, and lived experience materials.

- Feedback emphasised the value of clear, and structured organisation/ facilitation of such events.

4.7 POST-EVENT SUMMARY: FEEDING BACK

What happened?

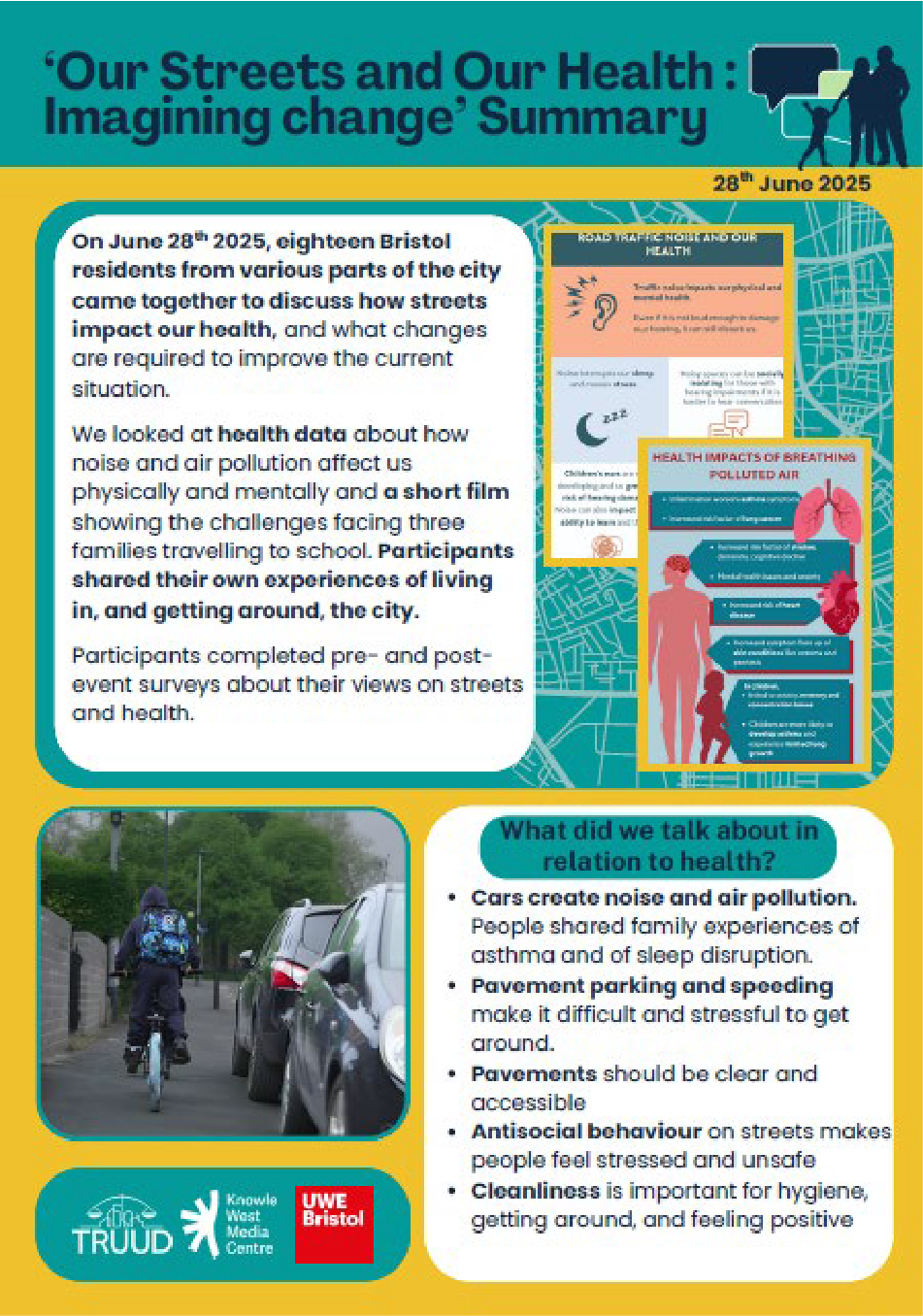

Within two months of the event, a 2-page summary of the proceedings was prepared and sent out to participants.

The summary had images of the posters to remind participants of the materials used (including a film still) and the focus of discussions. The summary also included the illustration from the event, and some anonymised quotes extracted from the event surveys.

In a real – rather than test / research – engagement event, summaries would include how the information collected from the discussions is being used and how it is shaping the design of an intervention. This approach is based on the principle of good engagement highlighted in Section 2.4, concerning transparency of process and continued dialogue. Our example demonstrates how the outcomes of an engagement session can be broken down into a simplified and visual representation.

During the session, and ahead of participant sign-up, we were transparent about the event providing a space to discuss links between streets and health, rather than contributing to specific local change, given it was run by researchers and not practitioners linked to decision-making.

Two-page summary sent to participants following the event.

4.8 SUMMARY OF LEARNING: CONSIDERATIONS FOR ENGAGEMENT DESIGN

The event demonstrated the value of using visually engaging, accessible materials that employ framing methods and incorporate health data and lived experience. Such materials can deepen understanding of key health-related issues at early points of engagement, and can be used to introduce discussions about the necessity of change.

The event also demonstrated the value of facilitating exploratory, deliberative engagement events where participants can discuss and respond to evidence and are given space to share and relate to each others’ experiences as well as exchange ideas.

This enables:

- greater contemplation of change which is collectively beneficial

- inclusion of lay knowledge

- discussions which feel more like co-discovery rather than a top-down imposition of ideas

- discussions which move towards strategic thinking about solutions.

These combined elements can provide an effective starting point for talking about change.

Based on our learning, key considerations for designing and running such engagement sessions can be summarised as follows:

- material preparation

- recruitment and session preparation

- facilitating and structuring the session

- evaluation.

Material preparation

- Creative materials are effective in conveying key information and evidence. These should be co-designed and tested with a group of public representatives ahead of engagement sessions to ensure they are accessible. This may require revising materials until they are the best fit (our materials required several iterations). Factor this into your timeframe.

- Incorporate framing in your materials (see section 3), using health framing strategies to introduce evidence and ideas which can pivot discussions around the need for change.

- Include materials which can help transmit information and prompt reflections as well as elicit emotional responses, promoting engagement in the issues being presented. Lived experience narratives sharing lay knowledge can be vital to this process.

- Consider which questions can best prompt focused discussion around your chosen materials when you plan your session.

Recruitment and session preparation

- Where issues are city-wide, recruit people from a range of areas and demographics to avoid discussions becoming heavily focused on particular, localised concerns.

- Be prepared for specific, localised concerns to be highlighted (see 3, below) and plan how to respond to these.

- Where possible, provide compensation for expenses related to attending the event including subsidising travel and childcare.

Facilitating and structuring the session

- Ongoing concerns around antisocial behaviour, poor services, insufficient housing, prevailing inequalities etc. may be raised and should be anticipated. Where concerns/priorities raised may not obviously relate to a session focus, well-informed, sensitive facilitation is required to acknowledge and respond to these, while keeping the session focused and on track.

- Allow a discursive, exploratory conversations to enable people to feel heard and connect with each other. Allow generous time for building understanding, whereby people can develop foundational knowledge and also share experiences and concerns.

- Consider how the questions posed will enable discussions to stay focused. Be specific and use clear language.

Evaluate

- Collect feedback from participants on the materials used and the session overall to help improve the quality of future engagement sessions.

- Provide a summary of the session to participants, highlighting their contributions and how these will be used. This demonstrates that their time is valued and ensures transparency of process.

4.9 REPLICABILITY AND TRANSFERABILITY

- Our test was not connected to a real life, specific street improvement or other built environment initiative. Given its hypothetical nature participants’ expectations and responses may have been different compared to those associated with an event related to a live intervention and facilitated by local government officers.

- Participants were from the general public from across a particular city, not a localised group with potentially urgent, area-focused concerns, as might be the case in real-life engagement scenarios. Even in our event there was a need to redirect focus to the specific session aims; this will be even greater amongst a localised population.

- While the approach described is replicable in an online context (online engagement event) it was not tested using this medium; more learning might have emerged from this.

- In a real case scenario time and resources available for early in-person engagement sessions may be limited. While these live sessions are essential some of the learning from the test event could be applied for wider communication purpose (e.g. use of framing to communicate evidence and sharing of lived experience through social media, websites etc to communicate the need for change prior to in-person engagement).

- Our event did not include representation from young people (16 – 20 year olds).Different outreach, event format and facilitation would likely be required to ensure the meaningful participation of this demographic group.

▲ Photo of test event, M. Black

REFERENCES

- Bailey, N. (2010). Understanding Community Empowerment in Urban Regeneration and Planning in England: Putting Policy and Practice in Context. Planning Practice & Research, 25(3), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2010.503425

- Kwiatkowska, R. (2016). Public Access to Information. Faculty of Public Health. https://www.healthknowledge.org.uk/public-health-textbook/medical-sociology-policy-economics/4c-equality-equity-policy/public-access-information

Funding statement

Our partners

Funding statement

This work was supported by the UK Prevention Research Partnership (award reference: MR/5037586/1), which is funded by the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Health and Social Care Research and Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Natural Environment Research Council, Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), The Health Foundation and Wellcome.

Our partners

v2.23